Contents: Species, Identification, Song, Distribution, Diet, Nesting Behavior, Nestboxes, Monitoring, Nesting Timetable, More Info, and Video Clip of HOSP Attack.

Note: the primary focus of this webpage is information relevant to House Sparrow population control.

control.

See more pictures of nests, eggs, young and adults.: Worldwide, there are 12 recognized subspecies of the of (English) House Sparrow, Passer domesticus or HOSP, with the U.S. bird descendant from Passer domesticus domesticus. Many sources say that the House Sparrow is not actually a sparrow, but is a weaver finch. It is now classified as an Old World sparrow bird. (Remember – just because a bird has “sparrow” in its name doesn’t mean it’s a House Sparrow!) More.

Identification: See HOSP description; photos of adults, nests, eggs and young; and other brown birds sometimes confused with HOSP. They hop when on the ground.

Song: It’s “song” is a single cheep (up to 4 types). Males cheep continuously, 60-100 times/hour, with unmated males calling more often. Females do not cheep much (4 calls/hour) unless they are trying to attract a mate. They tend to sing less during cold or rainy weather and short winter days. Listen to song and see video clip.

Distribution: House Sparrows are one of the most abundant birds on the North American continent, and are found throughout the populated world. They are common in agricultural, suburban, and urban areas. The only areas they tend to avoid are woodlands, forests, large grasslands, and deserts, and frozen wastelands. (In North America, they normally are not found farther north than about Fort Nelson, British Columbia.) Other than that, a sparse population of House Sparrows generally indicates a sparse population of humans, as they are synanthropic. HOSP have no established migratory pattern – they are year-round residents. Supposedly 90% of adults stay within a 1.25 mile radius during nesting season. Flocks of juveniles and nonbreeding adults will move 4 to 5 miles from nesting sites to seasonal feeding areas.

Diet: Mostly grains, wild and domestic; weed seeds; insects and other arthropods during breeding season. Forages on the ground for seeds. May pierce flowers to get at nectar. 60% livestock feed in fields, as waste feed, or from animal dung (wheat, oats, cracked corn, sorghum); 18% cereals (grains from field or storage); 17% weed seeds (major species: ragweed, crabgrass, bristlegrass, knotweed); and 4% insects. Urban birds eat mostly birdseed (including millet, milo, and sunflower) and food waste (bread, restaurant waste, etc.). Nestlings diet is about 68% insects, and 30% livestock feed on average. For young 1 – 3 days old, invertebrates make up 90% of diet decreasing to 49% by 7 days. Insects fed include what is abundant, including alfalfa weevils, bark beetle larvae, periodic cicadas, Dung beetles, and Melanoplus grasshoppers. BBS Map

Mating and Nesting Behavior: Males aggressively defend their chosen nest site, spending nearly 60% of their perching time at nestboxes during reproduction. They will attack adults of other species, peck eggs and kill or remove nestlings from nestboxes. Occasionally male HOSP attack other male HOSP and female HOSP attack other females. Females usurping other HOSP nests regularly commit infanticide.

HOSP are said to be monogamous, but appear to be more closely bonded to a nest site than a mate (i.e., if a mate is lost, they remain at the nest site trying to attract another female.) In one study (Sappington 1977), mated pairs remained faithful to each other only for 60.5% of cases during a single breeding season (Sappington 1977) and there was no evidence that pairs remained together for 2 consecutive breeding seasons. 39.5%of males had more than one mate during a single season. Sappington also found that 86% of nest sites were retained by a male for the entire breeding season versus 45% by the female. In subsequent breeding seasons, only 10% of the males returned to their previous nest site.

Females prefer males with a larger bib size; males with larger bibs are more active sexually and may have higher levels of testosterone.

Sex ratios of male to female HOSPs in breeding areas are probably close to 1:1 (Summers-Smith 1963, Wil 1973, North 1973, Sappington 1977.)

Nestboxes: HOSP can and will use any nestbox suitable for bluebirds. They do not need nestboxes, and will nest just about anywhere. Females prefer hole-type nests over tree nests, but there is no imprinting on the parental nest site. Frank Navratil determined that for entrances:

- ROUND

1 1/4″ diameter allows HOSP entry.

1 1/8″ diameter usually stops entry. - HORIZONTAL SLOT

1 1/2″ x 1″ slot allows entry.

1 1/2″ x 7/8″ stops entry. - VERTICAL SLOT

1″ x 1 1/2″ slot allows entry.

7/8″ x 1 1/2″ slot stops entry.

However, smaller birds may be able to enter smaller holes. Size depends on latitude and winter temperature, with smallest birds along the Louisiana and s. California coasts and in Mexico, and largest birds in Canada and the Rocky Mountain and plains region.

Monitoring: Nestlings may prematurely fledge 10 days after hatching. The nest may contain fleas, blow fly and/or mites (Pellonyssus reedi.)

- Timing: Nesting activity is most intense from February through May. The first brood per season March through April; subsequent broods and re-nests continue through August. Potential nest sites may be selected in fall (with the male displaying at a nest site) and used as winter roosts.

- Nest site selection: The nest site is selected by the male. HOSP use natural cavities created by other birds, nestboxes, or various other sites. While they prefer to nest in cavities such as a nestbox, they will nest in protected locations such as rafters, gutters, roofs (including clay tiles), ledges, eaves, soffits and attic vents, dryer vents, holes in wood siding, behind shake siding, dense vines on buildings, loading docks, roof supports, commercial signs, behind or above pipes and ductwork on buildings, wall voids, evergreens and shrubs. May reuse nests of Bank, Barn or Cliff swallows, Eastern Phoebes, American Robins, and Northern Orioles, and even alongside osprey nests, often adding nesting material.) Nests are often in 8-30 feet off the ground, which may afford additional predator protection.

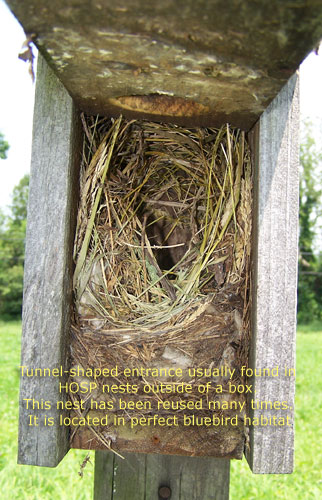

- Nest construction: Both the male and female quickly construct the nest, which is a loose jumble of odds and ends, including coarse grass (with seed heads), cloth, feathers, twigs and sometimes litter. Mid-summer nests sometimes contain bits of green vegetation (mustards or mints.) The nest is tall, and may have a tunnel like entrance particularly when built outside of a nestbox. In a nestbox, it may have more of a cup shape, and may be built up to cover sides of box. Nests in trees are usually globular structures with a side entrance, a squashed ball 30 – 40 cm diameter. In trees, forked or dense branching provide an anchoring platform for nests. Neighboring nests may share walls. See photos.

- Egg laying: In breeding season, may begin nest building just a few days before first egg. One egg is laid each day, 1-8, average 4 to 5. Eggs are cream, white, gray or greenish tint, with irregular fine brown speckles, shell is smooth with slight gloss. See photos. The background color can vary, the color of the spots can vary, the thickness of spotting can vary, and the size can vary. The last laid egg has less dense markings. Eggs with male embryos are slightly larger.

- Incubation: Usually begins with the penultimate (next-to-last) egg of a clutch, and is primarily by the female , lasting 10-13 days. The male sits on eggs from 16% of time early in incubation to 46% of time by days 9–12; the female from 60% at start to 46% at end. Male sessions average 9 minutes, females 11 minutes. Sappington recorded the male relieving the female 5 or 6 times a day for 20 minutes at a time, but he does not develop a brood patch, so he questioned whether this is truly “incubation.” He found only the female sat on the eggs during the night. (Sappington 1977)

- Hatching: Eggs hatch 11 days after the last egg was laid, typically in one day but may cover about a 1 to 3 day period. (See photo of newborn HOSP.) Hatching success may range from about 61 to 85%. (Mitchell et al. 1973 to Seel 1968.)

- Development: Hatchlings are red, fading to pink or light gray after 6 – 10 hours. The mouth is red, and the rictal flange is yellow. At 6 days, feather sheaths on ventral and dorsal tracts and wing coverts split. Feathers begin to fan at 7–8 days. The female primarily broods nestlings, with time decreasing as they grow older. Both parents feed (15-20 visits/hour) young by regurgitation; males feed about 40% of the time.

- Fledging: usually 14 -17 days after hatching. Young are capable of more or less sustained flight upon fledging. Prior to fledging, nestlings may become very quiet, lying crouched in the nest. Nests with fewer birds may fledge earlier (Kendeigh 1952) but another study did not find this (Moreau & Moreau 1940.) On the day of fledging, parents rarely feed the young, and fledging typically occurs in early morning over 1 to 3 days. Young stay with adult male for a few days, then gather with other young into foraging and roosting flocks. They are independent (feeding themselves) 7–10 days after leaving the nest.

- Dispersal: Birds generally remain near breeding colonies. Shortly after fledging, perhaps 50-75% of juveniles may wander 0.6-1.2 miles (1-2 km) (some sources 3.8-5 miles [6 to 8 km] to new feeding areas. Breeding individuals generally stay within this same range. Densities may be as high as 3108-3367 birds/mi2 (1,200 – 1,300 individuals/km2) around dwellings associated with livestock; average of 518/mi2 (200/km2) in rural areas (Dyer et al. 1977).

- Number of broods: House Sparrows may raise 2-4 (often 3) clutches each breeding season. (I thought I read a maximum of 5 somewhere.) Nests may be reused, with a re-nest or subsequent brood typically beginning 8 days after nest failure or after young leave nest (up to 10-49 days, usually 3-17). Birds experiencing failures may initiate clutches up to eight times in a nest during a single season. Some nests are reused 6 times. Cases have been seen where the eggs of the next clutch were laid while the young were still in the nest (Lowther, Bird Banding, 1979).

- Post-nesting: Birds tend to use communal roosts in the fall and winter months, versus their nest sites (Sappington 1977).

- Longevity: The record for a wild bird was 13 years and 4 month (Klimkiewicz and Futacher 1987). First-year survival of young is 20%; annual survival for adults is 57%.

Diseases and Body Parasites: (Also see other problems associated with HOSP) Viruses: colds and canary pox. West Nile Virus and Western Equine Enchephalitis. Bacteria: Bacillus anthracis, Mycobacterium, Salmonella pullorum, Treponema anserinum, equine encephalitis. Fungi: Aspergillus fumigatus, sarcosporidium. Protozoans: coccidia (very common), Lankesterella (Atoxoplasma) garnhami. Trematodes: Collyriculum faba, Prosthogonimus ovatus. Nematodes: Capillaria exile, Cheilospirura skrjabini, Microtetrameris inernis. Mites: Megostigmata sp., Ptyloryssus nudus, Proctophyllodes passerina, Dermoglyphus elongatus, Glycophagus sp., Dermanyssus gallinae (in nest), D. avium, Microlichus avium. Mallophaga, Amplycera: Menacanthus annulatus; Ischnocera: Bruelia cyclothorax (= subtilis), Philopterus fringillae, Degeeriella vulgata, Myrsidea quadrifasciata, Cuclotogaster heterographus. Fleas: Ceratophyllus gallinae, C. fringillae. Hippoboscid flies: Ornithomyia fringillina. blow flies? Protocalliphora sp. Ticks: Ixodes passericola, Argas reflexus, Haemaphysalis leporispalustris. Hatching failure sometimes due to microbial infections. (Source: Birds of North America Online summary.)

References and More Information:

- Lowther, P.E. (2006). House Sparrow. (Passer domesticus). The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Retrieved from The Birds of North American Online database: .

- 1977. Population dynamics, pp. 53-105 in Granivorous birds in ecosystems (J. Pinowski and S. C. Kendeigh, Eds.). Internatl. Biol. Progr., Vol 12, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

- Sappington, James N., (1977), Breeding Biology of House Sparrows in Northern Mississippi. Wilson Bulletin 89:300-309

- The Birdhouse Network, Cornell, Species Accounts

- USGS Patuxent Wildlife Center

- On this website (sialis.org):

- HOSP Management (active and passive methods)

- Are House Sparrows Evil? – by E.A. Zimmerman

- House Sparrow History

- When HOSP Attack

- Euthanizing House Sparrows

- Wing Trimming

- House Sparrow photographs (useful for ID – nest, fledglings, adult male and female) – also see Other Brown Birds Sometimes Confused with HOSP

- Nest and Egg ID

- HOSP Proliferation

- Handouts- HOSP Advisory

- Nest and Egg ID (with links to species biology and photos of nests, eggs and young) for other small cavity nesters

- Eurasian Tree Sparrow – sometimes confused with HOSP

All solutions to HOSP control have drawbacks, but not controlling them at all has the greatest drawback.

– Cherie Layton, The Bluebird Nut, 2006