“Without question, the most deplorable event in the history of American ornithology

was the introduction of the English Sparrow.”

-W.L. Dawson, The Birds of Ohio, 1903

Warning: This webpage deals with both active and

passive means of managing House Sparrow (HOSP) populations. House Sparrows are deadly and difficult, but there are ways to manage them.

QUICK TIPS: Successful bluebird landlords do not tolerate House Sparrows (HOSP), which are non-native nest site competitors. In my opinion, it is better to have no nestbox at all than to allow House Sparrows to breed in one. The combination of methods I recommend most highly are:

- Do not feed cracked corn, millet or bread. Switch to black oil sunflower, thistle and safflower instead.

- Use a Magic Halo at feeders.

- Try Gilbertson PVC nestboxes, as they are least preferred by HOSP. Troyer style boxes may also not be preferred.

- Hang monofilament on nestboxes early in the season (carefully).

- *For backyard boxes or small trails: if you do nothing else, put a sparrow spooker on top of the box after the first bluebird egg is laid (provides 24/7 protection for eggs, nestlings and adults.) Remove it after fledging so House Sparrows don’t get accustomed to it.

- Systematically remove nests and eggs that you are sure are House Sparrow nests every 10-12 days, or addle eggs.

- Trap early and often.

Although trapping is not for everyone, it is the most effective long term solution.- Consider using a Van Ert trap to trap a HOSP entering or claiming a nestbox (monitor hourly)

- (If populations are high) use a ground trap like the Deluxe Repeating Sparrow Trap with a live decoy. I ground trap continuously during active nesting season.

- Adult HOSP, nests, eggs and young may be destroyed under U.S. federal law. Humanely euthanize trapped birds. Relocating them only relocates the problem, and in some states a permit is required. If you cannot bring yourself to euthanize (see accounts of HOSP attacks before deciding – warning, graphic photos), at least trim their wings.

- Consider not putting boxes up at all in HOSP territory – try other areas instead.

After using these methods over a three year period, HOSP are no longer a serious issue on my trail.

CONTENTS:

- The Problem

- Recognizing a HOSP Attack

- Identification of House Sparrows

- Management

Choices- Passive Control: (discourage birds from nesting)

- Feeding

- Magic Halo

- Nestbox

Location - Clustering and pairing Nestboxes

- Nestbox Type

- Nestbox Color

- Light

- Hole Restrictors/Reducers

- What doesn’t work

- Monofilament (fishing line)

- Sparrow

Spooker - Removing Nestboxes altogether

- Exclusion

- Hirbonbec Pendulum (for Tree Swallow nests)

- Plant Management

- Chemical Repellents

- Active Control: (interfere with nesting process or HOSP themselves)

- Increased Aggression/Revenge/Rampage

- Dealing with a Wary Male/Difficult to Trap HOSP

- Traps

- Decreasing odds of capturing non-target native birds

- Removing trapped birds for an inbox or ground trap

- Trapping in public places

- Temporary

Boxes or Changing Box Height to Enable Trapping - Nestbox

(Inbox) Traps - Remote Controlled Traps (including “fishing“)

- Do It Yourself (DIY) links

- Ground Traps

- Sticky

Mouse Traps - Mist nets

- Wing Trimming

- Driving from Roosts

- Removal

of Nests/Eggs - Rendering Eggs

Infertile (Addling) - Guns

- Electricity

- Other Methods

- What Doesn’t Work

- References

and Links

- Passive Control: (discourage birds from nesting)

Also see: HOSP Photos of adults youg and eggs, HOSP egg photos, HOSP nest photos, History, Attacks (warning: graphic photos), photos and descriptions of other brown birds that look like HOSP, Behavior, Biology, Population Proliferation, Video Clip of HOSP Attack, information on euthanizing captured birds, HOSP advisory handout for people with boxes used by HOSP and one for commercial facilities allowing HOSP to breed/roost/feed, trap review, and essay “Are HOSP Evil?” Separate webpages with drawings and photos on sparrow spookers, Magic Halo, and How to Trim Wings and Links for more information and DIY drawings. Also see ongoing experiments to deter HOSP and Bluebird Widows/Widowers/Orphans.

THE PROBLEM

If you want to attract bluebirds, you will have to deal

with House Sparrows (HOSP) if they are common in your area. HOSP are probably the number one enemy of bluebirds and purple martins. Unlike starlings, they are capable of entering the 1.5″ round hole of a nestbox. HOSP have been observed threatening and attacking 70 species of birds that have come into their nesting territory. One study showed HOSP reduced reproductive output of a barn swallow colony in MD by 44.7% over a four year period. (Weisheit and Creighton, 1989). They may also steal nesting material, slowing down breeding.

You might think they’re cute (some bluebirders refer to them as “rats with wings”), but they attack and kill

adult bluebirds (warning: graphic photos), sometimes

trapping and decapitating them in the nestbox and building their own nest on top of their victim’s corpse. They destroy eggs and young. At a minimum, they often harass native birds (especially more timid species like

chickadees) into abandoning nestboxes. A HOSP flock near a nestbox can also cause premature fledging. In addition, they overwhelm bird feeders, driving other species away. (They are also voracious. Ben Lincoln reported that 16 HOSP went through 3 lbs. of birdseed over a two day period.)

If you are serious about bluebirding, you should be serious about HOSP control. Please do not put up a nestbox if you are unable or unwilling to monitor it and prevent HOSP from nesting.

For those who find it hard to deal with HOSP, here are some accounts of experiences repeated all too often:

- “I pray that you never have to experience the shock of opening a nestbox to find a nest full of babies, mutilated and dying, or on the ground, covered with ants, or broken eggs, or a blood-covered mother bluebird who fatally tried to protect her young.

- “I had bluebird pair nest in my purple martin house. Given 11 other compartments to choose from, the House Sparrows still killed the nestlings.”

- “If you ever happen to see a bluebird enter a nestbox, followed by a “Passer domesticus” or

House Sparrow, you might experience what I did minutes later–holding a beautiful male bluebird in your hands, bloodied and blinded by the attack, taking his last dying breaths.” - More quotes (Warning: includes graphic photos)

I have heard reports that in some areas HOSP and native cavity nesters appear to peacefully coexist. This may be due to a less aggressive HOSP population. It may also be because these HOSP have not become accustomed to using nestboxes, as they do not require cavities to successfully nest. I wonder whether this situation would change as local HOSP populations increase or when HOSP learn that nestboxes offer better protection from weather and predators. I often see reports of people who say they have had HOSP for years, and then suddenly start seeing attacks. It is usually just a matter of time. Regular trapping makes it easier to get younger birds before they get “educated.”

House Sparrows cause other damage: to crops (esp. grains) and gardens (eating seed, seedlings, buds, flowers, young vegetables [such as peas and lettuce], maturing fruit (such as cherries, pears and peaches but not grapes). They eat stored grain, and consume and spoil livestock food and water. They may spread other agricultural pests (such as nematodes and weed seeds). In exceptional cases (e.g., consumption of alfalfa weevil and cutworms), HOSP have been somewhat useful during nesting season as a consumer of insect pests, however under normal circumstances its choice of insects is often unfavorable (Birds of America, 1917).

HOSP droppings and feathers create janitorial problems as well as hazardous, unsanitary, and odoriferous situations inside and outside of buildings and sidewalks under roosting areas. They can contaminate and deface buildings with their nests and acidic droppings, which can damage the finish on automobiles, block gutters (with nests), and create fire hazards (e.g., when nesting around power lines, lighted signs or electrical substations, in dryer vents.) HOSP may peck rigid foam insulation inside buildings. (Fitzwater)

Last, but not least, they are also a factor in dissemination of about 29 human and livestock diseases and internal parasites (Weber 1979) such as equine encephalitis, West Nile (they are carriers, but it usually does not kill them), vibriosis, and yersinosis, chlamydiosis, coccidiosis, erysipeloid, Newcastle’s, parathypoid, pullorum, salmonellosis, transmissible gastroenteritis, tuberculosis, acariasis, schistosomiasis, taeniasis, toxoplasmosis, and trichomoniasis; and household pests such as fleas, lice, mites, and ticks. Note that other wild birds may also have these diseases and parasites, but because of numbers and typical nesting locations in close association with people, HOSP may be more likely to transmit them to humans and livestock.

PROLIFERATION: House Sparrows may raise 2-5 (average of 3) clutches of 3-7 chicks each breeding season, (averaging 20 chicks per season) which fledge in 14-16 days. They start claiming nestboxes early in the season (February and March). One male may “claim” three or more nestboxes if they are clustered. Since they are relatively long lived (up to 13 years), one pair can at potentially quintuple the population in one year. “If unchecked, a breeding pair can grow to over 2,000 birds in two to three years.” (Bird Barrier America, Inc.) (Using some conservative assumptions, I calculated one pair could theoretically increase to 1,250 birds in 5 years.)

RECOGNIZING A HOSP ATTACK – also see photo of dead nestlings and more descriptions of attacks

- Head injuries are typical.

House sparrow attack. Photo by Bet Zimmerman Smith Adults or nestlings attacked by HOSP usually (but not always) have visible evidence of pecking/hematomas on the top of the head (sometimes leaving a featherless crown or back) and in the eyes. Victims of an attack may be found dead inside the box.

- Eggs may be pecked in the nestbox (but usually not a pinhole like a House Wren piercing); or removed from the box, and found nearby or underneath it – usually within about 23 feet (Weisheit 1989), with contents (unless they are later eaten by something else like ants.) Eggs may disappear one by one, during daytime.

- Small nestlings may be removed from the box and found nearby, dead or dying (note that predators will generally pick them up if on the ground for any length of time so they no corpses may be found). The young may have a broken neck only, or pecked heads/eyes.

- HOSP may harass parents so they are unable to feed young, which then starve. They will be seen driving the parents from the box.

- Afterwards, if the HOSP elect to use the box (which does not always happen), they may be seen perching on top of it, or going in and out. However, sometimes they do not use a box after an attack.

- HOSP may build their own nest on top of a corpse. See photos of nests and eggs.

- Their poop kind of looks like a noodle – white and gray in color.

- Both males and female HOSP will attack, sometimes teaming up. See more photos (warning: graphic) and accounts of HOSP attacks.

- NOTE: Another small brown bird, the House Wren will also peck eggs (usually two small holes), remove eggs from a nestbox and may remove very young nestlings. Shortly thereafter sticks usually appear. See info on how to deter House Wrens.

IDENTIFICATION OF HOUSE SPARROWS

The House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) is sometimes referred to as the English sparrow. HOSP are not native to the U.S. They were deliberately introduced in multiple locations in the late 1800’s, and are

now established throughout the lower 48 states. See HOSP History for information on their introduction and why they have proliferated, and HOSP photos for pictures of nest, fledglings and adults.

Adults are short, stocky birds, 5.75-6.25 inches long (smaller than a bluebird, larger than a chipping sparrow/House Wren) with thick bills. The back is brown with black streaks. Both males and females have a dingy grayish/buff breast without stripes. The tail is short compared to other sparrows. The song is an boisterous, non-musical, monotonous single-note chirp. (Listen.)

- Adult males have a black, v-shaped bib on the breast under the beak (darkest during breeding season, lacking in juveniles),

male and female HOSP – drawing grayish-brown feathers with a white horizontal bar on the wing, and gray on the top of their head with chestnut below(not a chestnut cap like the chipping sparrow.) The beak may be pink/yellow/brownish or even dark black.

- Adult females are much harder to identify, but are dull gray with a light streak at and behind the eye. They can be easily confused with other sparrows and brown birds.

- Juveniles: Young look like females but are more brown above and more buff-colored below, with pinkish bills, legs and feet.

Before using any active management methods, you

must be able to positively identify a House Sparrow! A

good bird book like Sibley’s is invaluable in this regard. Some other “brown birds” (SEE PHOTOS) sometimes confused with the House Sparrow are listed below. Of these, only House Wrens and rarely House Finches will use a nestbox. When in doubt, let it out!

- House Wren and Carolina Wren – smaller, long pointy beak, tail often held upright

- Chipping Sparrow – smaller, mature adults during breeding season have a chestnut cap, strong dark eyeline. Not a cavity nester.

- House Finch – plain head, striped/streaked breast. Rarely uses nestboxes.

- Eurasian Tree Sparrow – brown crown instead of the HOSPs’ gray crown, and a black spot on its cheek that the HOSP doesn’t have. Also non-native, will use a nestbox, slightly smaller than a HOSP.

- other song sparrows (e.g., white throated).

- Harris’s Sparrow – male has a black bib, but the head is black, and it is about 1″ larger than a HOSP, longer tail. Not a cavity nester.

- Brown-headed cowbird (female) – larger, legs are gray-black (not pinkish like a House Sparrow), with fine streaks on breast.

None of these birds (except the House Wren, which is native) will bother other cavity nesters. Generally only the House Wren and occasionally the Carolina Wren will utilize nestboxes with a 1.5″ entrance hole. Many, but not all, true sparrows have markedly striped breasts – HOSP do not.

A HOSP nest is a loose jumble of odds and ends, including coarse grass (with seed heads), cloth, feathers, twigs and sometimes litter, and occasionally a sprig of green vegetation or roots. It is often tall (arcing up the back of the nestbox) with a tunnel-like entrance. Eggs are cream, white, gray or greenish, with irregular brown speckles. IMPORTANT: SOME NATIVE BIRDS also lay speckled eggs. CHECK FIRST before removing nests! See EGG ID Matrix.

Droppings: HOSP may roost in nestboxes outside of nesting season. (If you have paired boxes, the male may roost in one box and the female in the other.) It may be difficult to tell what species is roosting from droppings. Keith Kridler says bluebirds normally have seeds from fruits or berries in their droppings. Chickadees and titmice and even HOSP normally have droppings without large seeds. Normally the House Sparrow male will have firm droppings or tiny noodle-shaped feces often deposited right below the entrance hole on the floor of the box. Also, the roof of the box may serve as a place for him to spend a lot of time singing and watching for a female, so he leaves a lot of droppings there. (A Mockingbird perching there will also do this but a Mockingbird at this time of the year is feeding on fruits and berries.)

MIGRATION: The HOSP is an intelligent, hardy bird with no recognized migration pattern. Although they are widely distributed as a species, adults generally remain within 2 to 6 km (1.24 – 3.8 miles) of where they hatched. Flocks of juveniles and non-breeding adults may move 6 to 8 km (3.8 – 5 miles overall)to new feeding areas.

My husband noticed that new HOSP seem to “appear” after a storm like a Nor’Easter – perhaps they get blown into new areas. They are common in agricultural, suburban, and urban areas. The only areas they tend to avoid are woodlands, forests, large grasslands, and deserts.

MANAGEMENT CHOICES

It is better to have no box at all than to allow House Sparrows to reproduce in one.

One bluebirder said “If one won’t – or can’t (totally understandable) – try to protect blues from HOSP, possibly a greater disservice is being done to offer boxes to blues in which they are near-certain to die than to offer no boxes at all….unprotected boxes often become HOSP factories.“

I do not believe that HOSP are evil (see discussion). However, I do believe they need to be managed to enable bluebirds and other native cavity nesters to survive and thrive. Unfortunately, most passive methods are limited in their effectiveness. If House Sparrows

are in your area, and you do not take steps to manage the population, the likelihood of successful nesting by native cavity nesters birds will be reduced or even eliminated.

House Sparrows are non-native invasive birds that are not protected by the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act or Canadian federal, state and provincial regulations. U.S. federal law permits removing or destroying HOSP nests, eggs, young, and adults. Generally, they may be removed by individuals using any method except poison, or at night with guns with lights. Be aware that some states and municipalities have issued statutes/ordinances that protect all birds, both exotic and native, and also may require a permit to trap or euthanize HOSP, or have other applicable requirements.

Some people feel that no animal should be physically harmed and will prefer passive management, and I respect that. There are a number of options available. However, be forewarned that, sooner or later, many people who stop short of trapping will lose eggs, young and adults of native birds to a HOSP attack.

Some people want to “let nature take its course.” However, as noted above, House Sparrows are not naturally occurring in the U.S., and were introduced by humans. If you allow HOSP to breed in any location, you will be increasing future competition for nest sites.

Some passive methods still allow sparrows to harass birds nesting in natural cavities, to harass and evict bluebirds as they are selecting nestboxes, building nests, and mating, and

to destroy eggs and nestlings. Therefore, a combination of both passive and active methods will be most effective. I am not insisting that you choose management method over the other – I can only share with you what works and what doesn’t. You must make your own personal choices.

Personally, I have not found that large HOSP populations can be successfully controlled without employing active methods. Initially, it may feel like sticking your finger in a dike, but you can get the population under control with courage, persistence and time. HOSP can be virtually eliminated in the area of a small trail using a combination of passive and active methods. You can create an almost sparrow-free zone or oasis locally. However, vigilance (maintenance trapping when new HOSP show up) is required. Because they are so prolific, skipping even a year can allow HOSP populations to rebound to problem levels.

In the meantime, find out the name and number of your closest licensed wildlife rehabber, as you may need their help when HOSP attack.

PASSIVE MANAGEMENT

Passive management involves discouraging HOSP feeding and nesting. With all deterrent methods, it is important to evaluate efficacy over time, as birds may become accustomed, or behavior may vary from season to season (e.g., breeding vs. fledging vs. roosting).

It is possible neophobia (fear of novel objects) may be a factor with HOSP being deterred by sparrow spookers, monofilament, magic halos, and different box styles. However, a HOSP will readily investigate a new wooden box that is put up.

Some of these methods may also deter desirable birds, but may be necessary until you get the HOSP population in your area under control. If you are in a suburban area, you will probably need to recruit neighbors into using the same methods. See the House Sparrow advisory you can give to people with neglected nestboxes where HOSP are allowed to breed, or who are feeding millet/cracked corn birdseed that attracts HOSP.

Note that some passive methods (monofilament, sparrow spooker) still allow HOSP to harass native birds as they are selecting nestboxes, building nests, and mating.

SPARROW SPOOKER

After a bluebird has claimed a box and laid its first egg, immediately install a sparrow spooker. When properly used, these are extremely effective, protecting the nest 24/7, and nesting bluebirds will readily tolerate them.

They can be made with one vertical dowel/stick that has two or three horizontal dowels/chopsticks extending out of the top, with 1/2″ x 6″ strips of mylar hot glued/duct taped onto them, hanging over the roof and near the entrance hole. See instructions and drawings. If properly constructed, a sparrow spooker is a life saver.

Several weather-resistant, ready-made versions are available commercially. See more info and instructions.

A Wren Guard (designed to deter House Wrens) may also reduce HOSP interest in a box (especially if they are harassing nesting bluebirds), as it obscures the entrance hole and may make entering the box more difficult. See more info and instructions. It too should also be put up after the first egg and removed right before fledging.

FEEDING

- Note that in some areas, HOSP will eat anything including suet, from any style feeder. Do not offer seed that contains white proso

millet (the little round seeds that come in many mixtures) or milo or cracked corn (or offer seed mixes with less than 35% millet and 15% cracked corn if you want to attract juncos, native sparrows, and mourning doves). - Do not feed bread.

- Safflower seeds, nuts, and thistle (niger/nyger/nyjer), and sometimes black oil sunflower seeds, may not be preferred by House Sparrows, but may be eaten if food is scarce, so selective feeding is not an effective deterrent. (Brad from Wisconsin reported that HOSP in his area prefer black oil sunflower to striped).

- If feeding thistle, choose a goldfinch style feeder that requires birds to hang upside down to feed (with the feeding port below the perch.)

- Put a hoop device such as the Magic Halo on your bird feeder, which repels an estimated 88-94% of HOSP in winter, 84% of summer. Other birds are not repelled. Hang hobby wire (28-30 gauge or the thinnest lightest weight you can find) from the hoop at 4 equidistant points, weighted with a fishing weight or metal nut so incoming birds do not get tangled in it. See more info on the Magic Halo.

- If other people in your neighborhood are feeding HOSP, talk with them and give them a copy of a HOSP advisory to explain the impact to bluebirds.

- Try feeding black oil sunflower seeds (which HOSP may eat) in Duncraft’s smallest “satellite globe” feeder (one portal) hung from a wire or string, so it swings in the breeze.

- Use seed port wires. In open port tube feeders with perches, bend a 10″ piece of flexible wire in half. Feed the wire through the port, loop it over one perch and pull it tight and tie it off around the other perch. The strands of wire make it harder for the sparrow to get seed out of the feeder, but do not affect finches, chickadees, nuthatches or other desirable songbirds.

- Trim wooden/plastic perches back to less than 5/8″ to deter HOSP, grackles and starlings.

- Use plastic mesh cut to fit in the bottom of a hopper type/trough feeders.

- At feeding sites, fishing lines spaced 2 feet apart should repel 89-98% of HOSP.

- For suet feeders, try feeding suet in a hanging cage, but only fill the cage half way so to force birds to cling to the bottom of the cage to feed. Neither starlings nor HOSP like to do this.

- Remove bird feeders altogether. After about two weeks or more, the HOSP may move on, and you can put the feeders back up. Start with a suet or peanut feeder, or a thistle sock.

- For agricultural operations, avoid careless feeding or grain handling that offers HOSP a lavish supply of food.

Nestbox Location, etc.

- Avoid placing nestboxes near farmsteads, feedlots and barns (which offer plenty of food, shelter and nesting sites), and human occupation (e.g., buildings or areas where people are feeding cheap birdseed).

- Place nestboxes 0.07 to 0.5 miles or more from buildings and farms, since HOSP are usually associated with human activity

- Timing: Since HOSP start claiming nestboxes early in the season (February/March) leave boxes closed until April 1 in northern states. You can stuff crumpled up newspaper in the holes or plug them with a bathtub drain plug.

- Leave boxes plugged (e.g. with a rubber drain plug available at the hardware store), until the desired occupant is ready to

move into the area (to prevent HOSP roosting and claiming boxes early in the season.)

- Leave boxes plugged (e.g. with a rubber drain plug available at the hardware store), until the desired occupant is ready to

- Try relocating boxes that have been claimed by HOSP in previous seasons.

- For a box claimed by a HOSP: Generally nothing will stop them from nesting except making the box unusable, which may encourage them to move elsewhere. You can:

- remove the box

- plug the entrance hole ($1.79 rubber drain plug from a hardware store fits in the 1.5″ hole or crumpled up newspaper)

- leave the door/roof open

- remove the door

- Some people suggest placing a rubber snake in a box claimed by HOSP to scare them off (with about a foot of the body and head sticking out of the box.) A HOSP may proceed to build its nest on top of the snake.

- Placing a cat food can/tub constantly filled with water on the nestbox floor may also deter HOSP from nest building.

- Height: Boxes 3 feet off the ground MAY not be preferred by House Sparrows, but should not be used for native birds where there are climbing predators (cats, raccoons). Note that some HOSP will nest near the ground, even 24″ high, especially if nest sites are in short supply.

- HOSP will nest in hanging boxes. Hanging the nestbox from a wire has been suggested as a deterrent, but HOSP will nest in a hanging/swinging box or gourd.

- If a HOSP shows an interest in a box that bluebirds have claimed, immediately lower the height (temporarily) of the bluebird house to about 4 feet. Put up another house a few feet away at a much higher height (around 7-9 feet) and if possible closer to a nearby house or other man-made building. The House Sparrow will often move

to the new, higher house. This can facilitate inbox trapping.

- HOSP apparently do not “imprint” on the nest site where they were born, but they may nest in a site where they roosted during the winter, so it is important to deal with roosting birds also.

- NOTE: In lieu of spending time on trapping, some people choose not to put boxes up at all in areas where HOSP exist, especially if they are not willing or able to actively manage HOSP populations. An option is to try boxes on a golf course or park far from residences and farms instead.

Clustering and Pairing Nestboxes

Putting up an additional box(es) does not DETER HOSP nesting. It is not possible to saturate an area with enough boxes so other species can safely nest. If you do use this method, monitor more frequently (e.g., 2-3 times per week, especially at the beginning of nesting season) and then trap HOSP attempting to use the extra boxes. If you do not, “House Sparrows will reward your kindness by killing your bluebirds….” – Bob Orthwein

Because HOSP are colonial nesters, they will nest in close proximity to other HOSP. HOSP have nested in boxes 10 feet apart (Daniel 1995.)

Also, perhaps out of an instinctive desire to reduce competition, HOSP may actually prefer a nestbox occupied by other birds even when it is surrounded by other empty boxes. They may also end up using or controlling both boxes.

As HOSP may actually be more attracted to boxes that have nesting material in them (?), remove HOSP nesting material after trapping, and clean boxes used by other birds after fledging. (See more reasons to periodically clean out boxes.)

If you only have one nestbox, HOSP may evict nesting bluebirds. If there is an empty box in reasonable proximity (e.g., one in front yard, one in back), the HOSP may choose the empty box, especially if the bluebirds are farther along in the nesting cycle. As noted above, in some instances, HOSP will still focus on the occupied box, but then perhaps the native birds will move to the empty box. This can give native birds a chance to start nesting, especially on a large trail.

On the other hand, a box may remain empty for weeks, and as soon as another native bird chooses it, HOSP move in.

However, providing additional boxes has the added benefits of providing additional houses for native species, and offers a choice to native birds (since there may be something about one nestbox they don’t like). If HOSP do start nesting in one of the boxes, they can be trapped during in the incubation stage and the other nestbox is not tied up while you are trapping.

Kate Arnold has noted that House Sparrows may settle down when tending to their nest, rather than rushing around to other nestboxes. She finds it is easier to catch both the male and female during the incubation stage, as their behavior is so predictable.

Orthwein reported good success with triple boxes (spaced 7 yards apart). He quickly trapped the male HOSP and cleaned out the box, and in 8 years did not have a bluebird or Tree Swallow killed or their nests usurped in these triple box sets.

With regard to pairing:

- If bluebirds are in one of a pair of nestboxes, and Tree Swallows are in the other box, they may work together to defend the boxes against HOSP.

- However, if there are no Tree Swallows, it’s POSSIBLE (pure speculation here) that pairing could distract the bluebirds (which may try to defend both boxes) and actually make defense efforts less effective.

- If a HOSP is nesting in a paired box, any bird investigating or using the other box may risk attack before the HOSP can be trapped.

Removing Nestboxes

Some people recommend not putting up nestboxes if there are HOSP in the area, as it may invite catastrophe. However, if control methods are used, bluebirds may be able to successfully nest while you work on a longer term HOSP control program.

Sometimes people have problems with HOSP and give up immediately, and take their boxes down. Keith Kridler noted that if you do this, the next generation of bluebirds will probably move down the street, perhaps into a nestbox that no one monitors or cleans, and no one will ever report that House Sparrows or Starlings continued to evict or kill bluebirds year after year.

Nestbox Type (Also see Nestbox Styles, Pros and Cons | Nestbox suppliers

NOTE: No nestbox suitable for bluebirds is HOSP-proof. HOSP are smaller than bluebirds, and thus can enter any hole a bluebird can fit through.

Be aware that even though HOSP may not “prefer” to nest in certain types of nestboxes, they may still enter them for the purposes of attack, and may use them if nesting cavities are limited or competition for sites is fierce. They may also enter them if they are being used by another bird, due to their competitive nature.

Monitors prepared to trap House Sparrows have the option of adding a HOSP-resistant box near a contested bluebird box. Bluebirds will usually move into the HOSP-resistant box. with House Sparrows taking the standard wooden box where they can then be trapped and euthanized.

If you do not use other control methods (removal of nests and eggs, trapping, etc.), you risk HOSP attacks and are enabling HOSP populations to explode.

Type of boxes HOSP MAY avoid or not prefer:

Again, despite claims you may read, so far, no one has invented a nestbox that HOSP will not use. One of the reasons HOSP are so widespread is that they are very adaptable. HOSP do tend to be wary of change, and may initially avoid a new type of box. But over time (or due to nest site competition) they may become accustomed to it, and use these boxes.

Unfortunately, some “HOSP-resistant” boxes are not ideal for bluebirds either in some way: e.g., too shallow for safety (allowing predator access), small interior space (especially a problem for Western Bluebirds), entrance hole is too big, or the experimental open top (Bauldry design) allows rain to enter and is not approved by NABS (and besides the open top does not deter HOSP over the long term). Thus, native birds using these types of boxes may have a greater chance of a failed nesting.

- House Sparrows may be reluctant to use a Gilbertson PVC nestbox or other boxes made of PVC pipe. Purchase Gilbertson box on Amazon

- HOSP may avoid a slot box (e.g., Efta or Hughes designs), perhaps preferring a circular hole and a deeper cavity. However, I have seen HOSP readily nest in a regular slot box. Loren Hughes has had few HOSP attempts in the Hughes slot box.

- The TROYER box is a shallow slot box that HOSP MAY not prefer.

- Shallow box: Put a block of wood on the floor of a nestbox to make it more shallow (3-5″ deep), and thus possibly less attractive to HOSP. Unfortunately, bluebirds are perhaps less likely to use a box that is less than 4″ deep, so you may wish to remove the block of wood if you are successful in having the HOSP abandon the box. There is some concern that starlings may be more likely to prey on eggs and young in a shallow box, however Davis (Bluebirds and Their Survival) indicated this seldom occurs.

- In my experience, HOSP do not avoid Gilwood box (for plans see NestboxBuilder.com.) HOSP in my area seem to actually prefer the Gilwood over regular NABS boxes. The Gilwood box has a small interior than starlings prefer, and the wire across the large entrance hole actually makes the hole smaller. thus preventing starlings from entering.

- In my experience, HOSP seem to be ATTRACTED to a Flying Nun box – perhaps the dome shaped roof reminds it of their nest construction.

- See other experimental boxes.

- See information on nestbox pros and cons.

Larger Entrance Facilitating Escape (two-hole box, Slot box, perhaps Peterson)

- A larger entrance provides an avenue of escape in the event of an attack. While these boxes will not protect eggs/nestlings from attack, they may at least enable adults to survive. IF the HOSP moves on (they can be very persistent), the native birds can proceed to nest.

- In this video clip of a HOSP attack, it looks to me like the elongated Peterson hole shape helped the second bird escape.

- Some monitors expect that a male, or an incubating female may choose not to abandon the nest if a HOSP enters.

- A two-hole box is not technically a HOSP-resistant box. House Sparrows will readily use them in the absence of bluebird competition. But Linda Violett of California has found that somehow Western bluebirds seem to learn to control the box, despite HOSP competition.

The large interior may have something to do with it (maybe the bluebird can maneuver better?)

- As noted above, the second hole provides an avenue of escape for adult birds in the event of an attack. Maynard Summer witnessed BOTH the male and female HOSP entering a two-hole box at once to attack and kill a nesting chickadee. But of dozens of HOSP/Western Bluebird battles in 2-holers over an eight-year period on Linda Violett’s trails, only a handful of adult bluebirds are reported to have been trapped and killed by HOSP in 2-holed boxes. Its use appears to have reduced HOSP problems on the Yorba Linda trail in CA, and no adult bluebirds have been killed in 2-holers by HOSP on an infested trail in La Mirada (see online log notes). Of course, eggs and younger nestlings cannot escape the box when under attack, regardless of how many holes it has.

- Also see experiments with light

LIGHT

Some speculate that HOSP prefer a dark, deep cavity. Others believe that light is not a significant factor, as HOSP will nest in the open (e.g., on top of a sign), although these nests tend to have a tunnel-like entrance. Varner (1964) felt that bluebirds also prefer darkness inside the box, so a design that lets light in might also deter bluebirds somewhat. The main concern is designs that let in so much light that the interior can overheat, or let in nasty weather.

- Open-top “Bauldry” boxes are no longer recommended by NABS. They have a 3″ hole in the top, covered with hardware cloth. Supposedly HOSP don’t like a wet nest. Unfortunately, it is not healthy for bluebird nestlings either, and can increase the likelihood of fatal hypothermia. These boxes may still be used by HOSP.

- One birding store owner tried covering the 3″ hole with Plexiglas (on the theory that light deters HOSP), but the heat killed the eggs and nestlings. However, he did indicate that bluebirds appeared to prefer these boxes (Zimmerman personal communication, 2004)

- Boxes with 1/2 of the roof made of Plexiglas (covered during warmer weather to prevent overheating) do not appear to deter HOSP long term.

- Boxes built with extra light entering the box (vents, slots, two holes, Plexiglas) are all used by HOSP. HOSP have been known to use a nestbox that has no roof at all. I don’t know whether they are really not PREFERRED by HOSP.

- Removing most of the wood bottom of the nestbox and covering it with circles of Plexiglas, or with 1/4″ hardware cloth so that the bottom looks open to a bird looking inside the nestbox does not work long-term (Kridler on Dick Walker experiment).

Experiments with light continue:

We know that HOSP WILL use a box that lets more light in (see above.) The question is, will they AVOID a box like this, or PREFER a box that is darker over a lighter one when given a choice? And will native cavity nesters use a box with a lighter interior?

The bigger entrance hole in the Gilwood (which HOSP tend not to prefer) or a 2-hole box does let in more light.

Loren Hughes experimented with drilling a 2″ hole in the side of the nestbox near the top. Then he stapled a 3″ square piece of plastic cut from a milk jug over the hole on the outside of the nestbox. Note that the plastic may become brittle over time, and need to be replaced. He tested coating it with KRYLON Crystal clear acrylic spray to see if it lasted longer. Initially, HOSP seem to lose interest in the box (possibly due to neophobia – fear of something new). Some HOSP packed grass against the acrylic to block out light. He discontinued this experiment.

Other Nestbox Design Issues

Do not include a perch on a bluebird nestbox.

House Sparrows find them useful in maintaining possession of boxes they have managed to occupy. (Zeleny, 1976). However, a HOSP can use a box without a perch.

Hole Reducers: For the smallest cavity nesters (e.g., chickadee,

titmice, nuthatch) use a hole reducer (smaller than 1.25“) to exclude almost all HOSP and protect eggs and birds in the nestbox. (Tree Swallows apparently require at least a 1 3/8″ hole.) HOSP tend to prefer a 1.5″ diameter hole. However, smaller HOSP may be able to enter smaller holes, and HOSP size depends on latitude and winter temperature, with smallest birds along the Louisiana and s. California coasts and in Mexico, and largest birds in Canada and the Rocky Mountain and plains region. Frank Navratil reported that for entrances (after HOSP were allowed to build nests, reducers were placed on boxes):

- ROUND

1 1/4″ diameter allows HOSP entry.

1 1/8″ diameter stops entry. (NOTE: Keith Kridler of TX has had HOSP nest in boxes with an exact 1 3/16″ hole. Phil Berry of FL reported HOSP entering via a 7/8″ restrictor used on a box with Brown Headed Nuthatches nesting.) - HORIZONTAL SLOT

1 1/2″ x 1″ slot allows entry.

1 1/2″ x 7/8″ stops entry. - VERTICAL SLOT

1″ x 1 1/2″ slot allows entry.

7/8″ x 1 1/2″ slot stops entry- Note: Mike Donahue of Seattle had a HOSP build a nest in a Violet-green Swallow box with this slot size.

- DIAMOND or SIDEWAYS OVAL HOLE

-

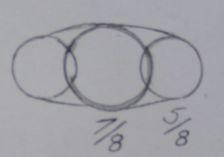

Oval hole for Violet-Green Swallows from Malcolm Rodin Malcolm Rodin has experimented with sideways oval holes for Violet-green Swallow boxes which he found deters adult HOSP if it is NO TALLER than 7/8″. He makes the hole using a 7/8″ and a 5/8″ Forstner wood bit. Drill three hole, using he 7/8″ bit for the center hole, and the 5/8″ bit for the holes on either side. Then file and sand to get a good oval shape, but do not exceed 7/8″ in height. The width will be between 1.5 to 1.75″ inches. See video on how to make.

- Gene Derig of Washington makes a wide diamond hold and has found it deters HOSP but allows Violet-green Swallow and chickadees to nest. The diamond he uses is 3.00″ wide, and the height is EXACTLY 7/8″ (this measurement is crucial.) The cut is straight lines all the way from peak to corner, and you can make it with just a chisel and a hammer. Derig does not use wood thicker than 3/4″, and files down the inside of the entryway to make it easier on the swallows.

-

- Note that as secondary cavity nesters, HOSP do NOT enlarge entrance holes – if this happens, the likely suspect is a woodpecker or squirrel.

- If a sparrow spooker doesn’t work for some reason (rare) and the babies are under constant attack by HOSP but are close to fledging, you could install a 1″ hole restrictor, which allows the parents to continue feeding but they will not be able to remove fecal sacs, and may have trouble accessing weaker nestlings to feed them. Remove the restrictor when the babies are due to fledge.

- Bob Orthwein noted “Even though house sparrows cannot enter the 1 & 1/8” entrance hole, these weird birds will often mercilessly harass nesting chickadees by hanging on the box, poking their heads in the entrance hole and attacking the chickadees entering and leaving the box. The sparrows will do this even with a nearby empty box that they can use. A wren guard stops this harassment.” See more information about how to make a wren guard.

- On a HOSP-infested park trail in CA, Linda Violett found that while boxes with a 1.25″ hole face guard that was about 3/4″ thick did not stop all HOSP action, it significantly reduced HOSP activity/interest. This may (?) be why I rarely catch HOSP in Van Ert’s Urban Sparrow Trap, which has a 1.25″ reducer on it to prevent bluebird trapping.

Decorative nestboxes should either have a hole 1 1/8″ in diameter or smaller, or the hole should be plugged or painted on. (See handout on unmanaged nestboxes, which can become HOSP breeding grounds.)

Floor size: Some people (e.g. Varner 1964) speculate that HOSP may prefer boxes with a larger floor size to accommodate their bulky nest. Thus a floor size of 3.5 x 3.5″ or 4 x 4″ may be less attractive to HOSP. Note that a smaller floor size can result in crowding (impacting sanitation, vigor, and increasing the effect of excess heat.) I have had HOSP readily nest in smaller NABS style boxes.

Can Trick?: For a nestbox with repeated HOSP nesting attempts, create an illusion that the interior is very small and cramped. The HOSP may then abandon the box. Take an empty small (e.g., 8 oz.) clean, dry tin can, and place it inside the box so that when the bird enters the entrance hole

they end up in the can. You can wedge the can in place with a small block of wood between the bottom of the can and the rear panel of the box. Leave it in place for about 2 weeks.

Once the HOSP abandon, perhaps a native bird will find and use the box.

(Thanks Rudy from Maryland).

Monofilament

For some reason, HOSP (but NOT bluebirds, Tree Swallows or chickadees) tend to be spooked by monofilament (fishing line)/hobby

wire. They will fly towards it, flutter in place, and then fly away. It may be due to their eyesight (since they are primarily seed eaters vs. aerial feeders) and flight pattern (approaching with wings spread.) Placing line on the roof may prevent HOSP from perching on it (which they tend to do when claiming/defending a box.) It is cheap, easy and quick.

HOWEVER, this effect often wears off over time, or when nest site competition is fierce. While not 100% effective, HOSP do appear to prefer nestboxes without monofilament over those that have it. This works better with adults, as juveniles are less fearful.

Put up the monofilament BEFORE the male HOSP starts looking for nesting sites and “bonds” with a box. Once he has bonded, he may tolerate it.

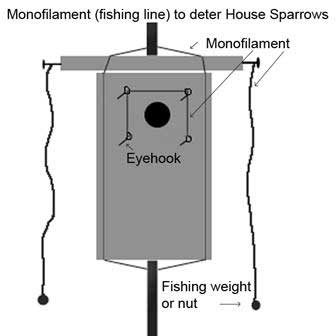

- String 6-20 lb. clear fishing line (pulled tight) on either side of the entrance hole (parallel). Fine fishing line may work better than thicker line, as it is “spookier.”

- The Bluebird Society of PA recommends spacing the line 1.75″ apart (on either side of the entrance hole.)

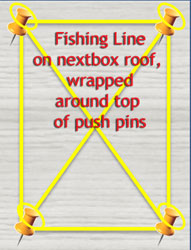

- You can use push pins or eye hooks to guide line. Make sure you can still open the door for monitoring. I also put two screws in the side of the roof and hang fishing line from screws.

- WARNING: To prevent the line from being pulled into the nestbox and tangling up nestlings, put a fishing weight or metal nut on the end of the dangling lines. Remove any fishing line that breaks or degrades over time. If loose monofilament ends up inside the box, it can kill a nestling or trap it so it cannot fledge. Dispose of line properly by cutting it up and throwing it in the trash.

- You can also string fishing line in an X-shape across all roof surfaces (suggestion from D Cass) as HOSP males tend to perch on the roof of a box they have claimed.

- Another layout shown in the drawing (which I haven’t used yet) involves four eye hooks surrounding the entrance hole, with the mono threaded through the eyes.

- Joel suggests using two 18″ metal fishing leaders (for pike etc.), crimped on 2 split shot weights, on 4 staples.

- Per the diagram to the right with fishing line set up shown in red, you can also stretch monofilament on either side of the entrance only. Lee Pauser did this, and did not have HOSP in such boxes for four years. The PA Bluebird Society recommends a space of just 1 3/4″ in between the parallel lines.

- A commercial version using fishing line, called a Sparrow Shield, is made on the principal of the Magic Halo (designed to deter HOSP from bird feeders.) The Sparrow Shield (designed by Gene Wasserman) is available for nestboxes from the Michigan Bluebird Society. It is very easy to screw into the back of a nestbox, and comes pre-made with four weighted fishing lines that dangle from a metal hoop over the roof.

Exclusion (e.g., from roosts)

Most HOSP go to their main roost 15–30 minutes before sunset. Note: Some

sources say that HOSP are not “hardy” outside in cold weather, and that one week of temperatures at or below 10*F will decimate the sparrow population (even if they have adequate food) if they cannot get into warm building to roost at night. Once their favorite spots (cavities in buildings) are gone, the HOSP are more likely to go into a trap box.

- DO NOT PROVIDE ACCESS to bird seed, grain, or food waste. SCREEN poultry houses and livestock feeders to exclude sparrows. Seal or block all openings larger than 3/4.” CLOSE OFF ALL OPENINGS in warehouses, garages and farm buildings. Options include the following:

- Put up plastic BIRD NETTING (attached with tacks or pieces of lath), or wood, metal, glass, bell towers, eaves, masonry, or 3/4″ rust-proofed wire mesh (hardware cloth) over upper structures where HOSP can roost or nest (like rafters and ventilator openings that provide access to buildings – see photo.) This can work on carports.

- On ivy-covered walls, string green/black plastic netting, or remove vegetation.

- REPLACE OR COVER BROKEN WINDOWS in upper stories with wire mesh, plastic, wood or sheet metal.

- BLOCK OPEN DOORWAYS with full-length, hanging plastic strips (4 to 6 inches/10 to 15 cm wide)

- SIGNS: Attach signs flat against buildings. Screen or block spaces between existing signs.

- USE ‘GREAT STUFF’ EXPANDING FOAM to fill and/or seal up cavities in out-buildings and barns. Wad up scraps of chicken wire or window screening and stuff them into any place that you see HOSP trying to nest, then squirt in ‘Great Stuff.’ After it dries/hardens, shave off the excess that oozes out. You can paint right over the dried/hardened foam. The wire mesh/screening material deters persistent HOSP who can use their beaks to reopen holes that are only filled with foam.

- Block the spaces between air conditioners and buildings.

- If possible, place fine mesh over architectural decorations on older buildings.

- Work with architects on building designs to eliminate ornamental patterns and holes that provide nest sites for sparrows.

- ELIMINATE ROOSTING AND NESTING PLACES in new building design/alter older buildings

- ELIMINATE PERCH SITES by fitting ledges and rafters with slanted boards (metal, Plexiglas or wooden)at a 45 degree angle, such as those under shopping mall overhangs or old buildings.

- PUT PLASTIC BIRD NETTING over high-value crops such as experimental grains. Do not leave openings in the bottom.

- MONOFILAMENT (fishing) line placed at 1 to 2 foot intervals may help repel HOSP from roosting sites. Place screws or nails to tightly wrap fishing line in place to create parallel lines.

- Note: Sharp metal projects such as Nixalite or CatClaw are expensive and will not work unless they are less than 1.5″ wide, so ledges and other niches must be completely covered.

Hironbec Pendulum on a Tree Swallow (TRES) box (Does not work with bluebirds, which are heavier than HOSP)

- Rene Lepage of Quebec invented the Hironbec Pendulum. This weighted pendulum, invented by attaches to the front of a wooden box. It allows lighter weight Tree Swallows (which weigh about about 18-21 grams) to enter a wooden box, but NOT House Sparrows (which weigh about 28 grams).

- See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PQT0YnHIFhM video showing how to set it up and adjust it. Thanks to to the Salmon Creek Tree Swallow Project for posting this and providing the guidance summarized here..

- It’s not a trap. It will even keep HOSP out of a box they are already using.

- Wait until the Tree Swallows have started nest building.

- If left alone, HOSP can figure out the pendulum. (If you want to keep HOSP out of the box until then, remove it, or cover it with a black plastic bag until TRES begin to nest.)

- At first, move the weight on the pendulum to the left so it doesn’t wobble when the TRES first start using it. Gradually move it to the TRES balance point over a few hours.

- Note that the male TRES may learn to navigate the pendulum later.

- Periodically check to make sure the pendulum mechanism doesn’t get jammed with nesting material (you want it to keep wobbling.)

- The Hironbec Pendulum can be purchased at www.hironbec.com (in French – see English version here: . A PDF instruction sheet can be downloaded at the website.

Plant Management

- Remove vegetation they congregate in while resting (e.g., privet hedges or hedgerows, multiflora rose, thickets, brush piles, and ivy growing on walls which may also be used for nesting), or cover with bird netting (the same stuff used to prevent birds from eating fruit off of blueberries, etc.) However, note that other native birds may use this vegetation also. Some shrubs or trees can be pruned to open them up (which is usually good for the plant too) so they are not as useful as hiding places for HOSP.

- Protect small crop areas with plastic bird netting in situations involving high-value crops, such as grape and berries. Do not leave any openings at the bottom of netted crop areas.

- Severely prune trees and shrubs with thicket-like branches used by HOSP as cover. This will also enable predators like Cooper’s hawks to hunt HOSP more effectively.

- Remove dead fronds from palm trees to eliminate roosting sites.

Chemical Repellents

Use of Bird-X “Bird-Proof Repellent Gel” is NOT recommended. Although it is advertised as “a non-toxic, sticky chemical that makes a surface tacky and uncomfortable to birds” it is, of course, not specific to House Sparrows. Any bird that lands on it may get it on their feathers, which can interfere with their ability to fly, resulting in death by falling/starvation.

Also see what doesn’t work

ACTIVE MANAGEMENT

Unfortunately passive methods have limited effectiveness. Active management includes rendering eggs infertile, egg and nest removal, HOSP trapping, shooting, etc. Since House Sparrows are classified as pests and are not protected by U.S. federal law, they may be quickly and humanely euthanized.

Trapping HOSP can dramatically increase successful nesting by native birds. After dedicated trapping, one trail monitor in California saw successful bluebird fledging almost double in the first year. Some monitors feel they would have nothing but HOSP on their trail if they did not trap.

Relocating a HOSP would be like trapping a rat and letting it loose in your neighbors yard. (A Purple Martin Conservation Association publication says “Some people choose to kill the birds, others transport them 10 to 20 miles away and release them. This latter option, while easier on some people’s conscience, really serves no purpose other than to waste fuel….House Sparrows may settle into the area where released, but they will cause others of their kind to disperse outwards. In other words, it’s analogous to trying to bail the water out of a boat by taking buckets of water from the back and dumping them in the front.”)

HOSP may need to be relocated 25 miles or more away. Relocating any wildlife without a permit is illegal in some states.

See Euthanizing HOSP for methods that have been used. Dead sparrows can be frozen immediately, and donated to raptor recovery centers to feed their injured birds. Contact the organization for details about what they will accept. They may also be suitable food for snakes.

PROVOKED HOSP AGGRESSION

The Potential for Increased Aggressive Behavior/HOSP Revenge Syndrome/Rampages in Response to Active Control Such as Removal of HOSP Nests/Eggs/Young

Steve Kroenke wrote an article on House Sparrow Revenge Syndrome. He posits that HOSP become even more aggressive in response to some active control measures, and may destroy and attack nests of other birds in the area. It is hard to know whether an attack would have occurred anyway, regardless of active management. It may not always happen, and it may not often happen. However, multiple people have reported HOSP taking over another box with an active nest when their own nest/eggs are removed, and in some cases attacking nests in one other box or multiple boxes but not subsequently using those boxes for their own nest.

Study of HOSP nest and egg removal on a trail (without trapping): Paula Ziebarth and Darlene Sillick conducted a study on this issue in Ohio. Based on results in the first year, it appears that HOSP nest removal, especially after eggs have been laid, is extremely dangerous for native cavity nesting birds. It may set up an “ecological trap” for native nesters that believe it is empty and available. Thus they enter to check it out, and may be attacked and killed. In a paired box situation, HOSP may abandon the box where they were unsuccessful (where the monitor just removed nest and eggs) and kill whatever they find in the adjacent box so they can use that one.

It is possible that loss of a nest/eggs may result in a spike in testosterone which triggers re-nesting, and/or more aggressive behavior. Although I’m not familiar with any scientific studies on this, Keith Kridler discussed a study where male HOSP injected with testosterone began vigorously defending their chosen nestbox and searched out and removed other cavity nesters using boxes close to their territory. It may also be a survival mechanism. (Note: the size of the black bib is an indicator of testosterone levels. Older males may have “learned” to be more aggressive than younger males.)

One trail monitor experienced an increase in HOSP attacks on trails in response to removing a nest, or all HOSP eggs prior to capturing the male; but NOT in response to egg piercing, or trapping and removing a male or female. Another experienced takeovers of other boxes upon removing a HOSP nest with eggs, but NOT in response to addling and replacing the eggs in the HOSP nest. On an experimental no-trap trail, a clutch of bluebird nestlings were killed after repeated HOSP nest/egg removal even though a sparrow spooker was on the box (a first for me.) Another bluebird landlord (AMP) had a similar experience after removing some (not all) HOSP eggs from an adjacent box.

Others believe the HOSP “rampage” concept is a myth. A trail monitor in California has destroyed dozens of HOSP nests and smashed hundreds of eggs inside and outside the nestbox, without witnessing any “HOSP rampages” or behavior that might be construed as retaliatory.

If your native chicks are close to fledging and you are concerned about the possibility of takeover/revenge/ rampage, I recommend that, to be on the safe side. it might be wise to wait to take certain active HOSP control measures such as removal of nests with eggs, or removal of the female only. (Trapping the pair eliminates that threat). In the meantime, I’d strongly recommend using a Sparrow Spooker on a nestbox being actively used by native birds if HOSP are in the area. Instead of removing nests and eggs, addle the HOSP eggs so they are nonviable and return them to the nest. (This will not help with single males which also build nests.) The safest, most effective solution is to trap both the male and the female to completely eliminate the possibility of an attack. Do not remove the entire nest until you trap the male. It is easier to trap HOSP with an active nest in the box. See inbox trapping.

Wing Trimming

After trapping a HOSP, you can trim both HOSP wings prior to release so they cannot attack bluebirds/enter nestboxes to reproduce. See photo demo and more info. Fawzi Emad reports that HOSP tend to become docile after trimming. This option is best in areas where the HOSP population is not huge. Using this technique, Emad reported that the population got under control in 2-3 years.

Trimmed feathers re-grow in about 6 months. (McLoughlin). It is important to trim both wings – if you only trim one, the bird will not be able to maneuver at all and will basically become cat food.

Driving Sparrows from Roosts

A 1912 Farm Bureau bulletin noted that sparrows frequently become a nuisance by roosting in ornamental vines and in crevices around buildings. If scared out late at night, several nights in succession, the may desert the roost. A stream of water from a garden hose is a potent ejector, particularly on frosty nights. This is a temporary measure. Some folks have also had luck “smoking out” HOSP from building rafters.

Do not allow HOSP to become “bonded” to your nestboxes by allowing them to roost in them over the winter. Occasionally check the box during winter months, and use an inbox trap as needed, or plug up the entrance (e.g., with a piece of cardboard or a rubber bathtub drain stopper.)

Removal of Nests and Eggs

WARNING: Before interfering with any HOSP nest or eggs, you must first be SURE it really is from a HOSP! It is illegal to disturb the nest of any native bird. People have confused nests of nuthatches, Tree Swallows and Western Bluebirds with those of HOSP.) Birds other than HOSP occasionally use “trash” in their nests, or may build an untidy nest. See photos of HOSP eggs, HOSP nests, a description of a HOSP nest and nest and egg ID. It takes about 27 days for HOSP to lay eggs and fledge young, so you have time to be sure of the ID.

You can try removing HOSP nests and eggs. On some trails this is enough to control HOSP populations. Occasionally birds take off after one or a few removals. However, since the male bonds with the box, they generally immediately rebuild, and drive off other native birds that might want to use the box.

Unfortunately with this method, the box is unavailable for use by native birds, or native birds may assume that the box is empty after nests are removed, enter, and be attacked by HOSP. HOSP may also come back and attack eggs/nestlings.

If you do remove nests, be prepared to do regularly (at least every 10-12 days), as HOSP rapidly rebuild.

If you have extra boxes, you can wait until the nest has been there for a couple of weeks (and has eggs in it) to cause the HOSP to “waste” more time and effort before removing the nest.

WARNING: Some people claim that males get enraged by repeated removal of nests or destruction of eggs, and will go on a rampage. Others feel this is a myth. I have had it happen.

If you are also ground trapping, save nests for use as lures.

Linda Violett has successfully controlled HOSP populations on a trail in California without trapping. She uses large two-hole boxes and removes nests and eggs. See her keys to success summary

Some (e.g., Fawzi Emad) indicate they have had success pairing a nestbox for HOSP with a bluebird box, letting the HOSP lay eggs and then rendering them infertile, keeping the HOSP occupied without allowing them to reproduce. I would still be concerned about the potential for territorial aggression by the male HOSP against birds in the paired box, and the loss of an available nest site for native cavity-nesters.

Use a long INSULATED pole with an iron hook on one end to remove nests located in high places like shopping malls and buildings. Try exclusion to prevent re-nesting.

If a male HOSP (or HOSP that nested previously in a box) bonds with a box, moving the box might help temporarily BUT HOSP usually quickly find the new location, and for some reason (competition?) HOSP are even more interested in a box being used by other species (vs. an empty box.)

Another option is to remove all eggs but leave one and allow HOSP to raise one chick to keep them occupied and to reduce attacks on other boxes. THIS IS NOT A PREFERRED OPTION as this nestling will grow up and cause the same problems that adult HOSP cause. The grown up may bond with the box and the territory.

Rendering Eggs Infertile

NOTE: If you use any of these methods, it’s important to visit nestboxes frequently to prevent re-nesting.

If eggs are rendered infertile, the female will generally continue to incubate them for some time (2-4 weeks, after which she will abandon the nest), keeping her from reproducing or competing with other nesting sites. IF NOT DONE PROPERLY EGGS WILL HATCH. The most humane approach is to render the eggs infertile as soon as laying has ceased and incubation begins. Incorrect or incomplete piercing and shaking can leave the embryo alive but deformed.

Mark treated eggs with a magic marker if the female is still laying. Also, sometimes birds realize the eggs are not viable, and remove them and lay new eggs, and you won’t be able to tell which are treated. Monitor weekly and remove unmarked eggs and either discard them or also render them infertile.

Addling is a good choice if the nest is not in a nestbox, which makes it harder to trap. However, it allows the HOSP to survive and breed elsewhere. Shake eggs vigorously. These eggs sometimes still hatch, so not the best method!

Refrigerating: (Recommended method.) Refrigerate and mark half of the eggs at least 24 hours; the next day do the second half. (If you put them in the freezer they will probably break. Coolling for 4 hours at 40 degrees F will render eggs infertile.) Let them warm to room temperature (e.g., in your hands) before replacing them – otherwise the HOSP may remove them. You might keep a supply of sparrow eggs in the refrigerator. Store them in a small craft “organizer”/bead holder with small compartments that protect each sparrow egg from damage (buy in the Wal-Mart craft section,) or in a container used for small Cadbury candy eggs or bubble gum eggs that are sold at Easter-time. This is especially useful when HOSP build nests in evergreens, etc., since they are harder to trap than HOSP who nest in a box.

Oiling: (Best choice after refrigerating) Dipping or rubbing eggs with 100% food grade corn oil keeps air from passing through the shell so the embryo cannot develop. Oiling is reported to be highly effective (between 95-100%). Coat the entire egg, and allow it to air dry before returning it to the nest. If you try to wipe the oil off, you might break the eggs. Do not wet the entire nest with oil, as it will get on the nestbox.

Piercing: Prick eggs so they will not hatch, and return them to the nest. You must break through the membrane that surrounds the egg white – a shallow prick is not sufficient to prevent hatching. Push a small-size needle or lance (used by diabetics to test blood – available at drug stores) into the large end of the egg. (A pin is generally not sharp enough.) The hole should be small enough so that the contents will not run out and alert the mother that the egg is damaged (at which point she may lay more). Be careful not to break the egg while holding it. Occasionally pierced eggs will hatch, so you might want to addle them first. Store the needle with the sharp point embedded in a cork.

Cooking: Boil them, microwave them (a few seconds on low or they will explode).

Refrigeration: Refrigerate overnight at 40 degrees F or below (at 45 or above they may remain viable, if frozen they may crack.)

Dummy Egg Replacements: Replace (swap)the real eggs with fake speckled eggs (about 0.9″ long) available at craft stores such as Michaels. This may not work as well as real eggs that have been rendered infertile.

The Sparrow Swap project found that swapping real eggs with replicas delayed HOSP from starting a new nest attempt, but it might encourage more frequent nesting compared to no management at all. However, it still has the potential to reduce the number of broods. HOSP do tend to lay another clutch more quickly after a removal versus after a swap.

LIVE TRAPS

There are several advantages to live traps. Sometimes neither law nor public sentiment will allow the use of firearms or poison. Traps are safe to employ. They also permit the use of sparrows for food (by humans, or by wildlife), as they leave the flesh uninjured. In addition, native birds can be liberated unharmed.

The two main types of traps are ground traps (baited and placed on the ground) and nestbox or inbox traps (used to catch a single HOSP entering or claiming a nestbox.) There are other types (mist net, bottomless pit, tipping can, etc.) that I am less familiar with. They are all live traps, which means they are not designed to kill the captured bird.

See review of various types by Paula Ziebarth.

If you only have a few HOSP, go with a nestbox trap, as they are less expensive, effective, and directly address the issue of proliferation and nestbox competition. They may also be more likely to catch the older aggressive male. My personal favorite is the Van Ert.

If populations are higher, get a ground trap. These may be more likely to catch juveniles and first year males. My personal favorite is an escape proof repeating trap like the Deluxe Repeating Sparrow Trap.

NOTE: Some states or localities may require a license or permit for any type of trap, even for non-native birds. CHECK! (E.g., in TX, a state-issued trapper’s license is required.)

To decrease the chances of catching or killing non-target native birds:

All traps must be checked frequently to ensure that only target birds are trapped. Release native birds immediately. They are not as hardy as HOSP. They may also be killed in a ground trap by other birds trapped with them, as aggression may increase due to stress and close quarters.

For ground traps, to reduce the likelihood of catching native birds:

- Use bait types not preferred by native birds, such as bread and millet.

- Use HOSP decoys. It won’t prevent other bird species from entering a trap, but it may deter them somewhat.

- Use traps designed for HOSP (elevator trap weighted specifically for HOSP, or trap with a tunnel like entrance vs. a Hav-a-Hart). Native birds are more likely to be caught in a funnel trap than in a weighted elevator trap.

- Elevate the trap off the ground (e.g., on a picnic table, milk crate, yew bush – if it’s on a shrub you won’t have to clean up underneath. Even a foot or two up will attract more HOSP.)

- To prevent mourning doves (which like cracked corn) from entering the DRST (they jam themselves into the elevator sometimes and can be seriously injured in the process) try putting two nails/screws on either side of the platform (to leave about a 2″ space in the middle leading to the elevator entrance), so only smaller birds can enter.

- WARNING: If you cannot monitor a trap for some length of time, or when storing the trap in an outdoor shed etc., do not leave any food in it, and disable it (e.g., use a twist tie or cable tie to wire it open, or turn it upside down). That way if a creature (mouse, native bird) goes in it, it will not die inside.

For inbox traps:

- Always check hourly during the daytime. Immediately release a non-target bird. No matter what anyone tells you, some native birds WILL go inside a box that HOSP are using, or an empty box when they are using another nearby. If you leave inbox trap up for a day or more without checking it, ANY bird trapped inside (including a bluebird) for too long WILL DIE.

- If it does not endanger a native cavity-nester using the box, wait until the HOSP have clearly claimed the box and begun building a nest.

- If you are using inbox traps on a trail, here is the technique P. Ziebarth uses: “I always make little trail notes on a small note pad and write “SET” (trap set) and circle it whenever I set a Van Ert [inbox trap]. Then I cross out the “SET” with a big X when I remove it. This way I never forget which box I have one in.”

- Use a 1.25″ hole reducer to exclude most bluebirds. However, monitor carefully: Small male bluebirds can squeeze in a 1 3/8″ hole. One monitor lost a Western Bluebird that went into a box with a 1.25″ hole restrictor on the outside, and lost a battle with a HOSP inside the box. Bluebirds (especially males) have a tendency to check out local real estate. This works better on a box where HOSP have already started a nest/have eggs and thus are motivated, as otherwise HOSP may avoid a smaller hole.

- If you do not use a reducer, you can drill a 1.25 “escape hole” in the side of a trap box to allow smaller birds like Chickadees and House Wrens to escape if trapped. Of course a bluebird could still end up being trapped inside, so the box must be checked hourly.

Removing Trapped Birds: Birds trapped in an inbox trap need to be removed immediately. HOSP in an ground trap should be okay for several hours. Here are some tips on how to remove birds quickly from traps without injury or escape. To transport a bird, place it in the cut off toe of a pair of panty hose, which still enables it to breathe but keeps it from escaping, or struggling and potentially injuring itself.

- Get a mesh laundry bag with a drawstring- the kind used for laundering delicates – found in Wal-Mart with ironing board covers etc. Don’t use regular mesh as the birds can get tangled in it. A strong clear garbage bag may be used. A dry cleaning bag is not strong enough. A cloth laundry bag with a drawstring can also be used, and may be less scary for the bird, but you will not be able to immediately determine whether it is a HOSP.

- Remove birds as soon as the trap is tripped.

- When removing birds from nestbox traps, cover the nestbox with a mesh bag, pulling the drawstring tight at the bottom, cinch it, or tie it closed with a pipe cleaner.

- Open the the box and HOSP will often (but NOT always) fly out into the bag. (Note: Some birds will stay inside the box and not immediately fly out into the bag, especially if there are live young inside.)

- Scrunch the bag closed underneath or around the bird when taking it off the box so it doesn’t escape.

- Remove the trap (unless you are going to try to catch the mate.)

- I don’t recommend trying to remove the birds by opening the nestbox door–you are too likely to lose them. Once a male has escaped a nestbox trap, he will be very difficult to recapture.

- Night Sneak: If you have a top opening box and good reflexes, or it is night time, you may be able to quickly slip your hand in while the bird hunkers down and grab it. I’ve had too many escapes with this approach. I wouldn’t want to end up with a snake (or a flying squirrel) in my hand either.

- When birds occupy barns or other enclosures at night, some people can catch them by hand by shingin a flashlight at them, which temporarily blinds them.

- If a bluebird or other non-target bird is trapped, they generally will not fly into the net. Instead they stay on the nestbox floor. Prop the door open and leave the area so the bluebird can exit.

- When you put your hand in the ground trap to remove birds or refresh food and water, they will flutter excitedly, and if you’re not careful, escape. Remove one bird at a time. If the door is small, cover it with your other hand while reaching in. Or hold a mesh laundry bag around the door such that any wayward bird would fly into it. Otherwise, you might devise some kind of plastic/rubber “guard” (flaps, or cut an X in it) that you can stick your hand through.

- Don’t be afraid to grasp them firmly (without crushing) by the body. Put your hand behind the head, encircling and holding their wings close to the body so they will not struggle. They may latch onto your hand with their beak, but it’s just a pinch–not painful. However, you may wish to use a pair of gloves. Do not attempt to grab them by the tail as the feathers will come out.

- Do NOT open up a trap inside a large building – if the trapped bird gets out, it will be unlikely to enter the trap again.

For traps where you can lift the trap door from the outside, hold a soup can (with both ends removed, and a plastic bag held on one end with an elastic bag) over the entrance hole. The bird will fly towards the light. Slip a piece of cardboard over the open end before removing the can.

Dealing with a Wary Male or difficult to trap bird: Male HOSP in particular can be difficult to trap, especially if they were trapped and escaped once before, or are older and wiser. HOSP in general seem wary of change, which is why a new nestbox style, monofilament or Sparrow Spooker may freak them out. Here are some techniques you can try with inbox traps:

- Try trapping overcast days with a light rain, when HOSP tend to sit tight on eggs/young.

- Use lures such as feathers, nesting material, grass/stick hanging out of entrance hole, placed below the trap box, and put a fake/real HOSP egg inside the nestbox.

- Reduce nest to 1 inch jumble and push it towards the back of box. Cover the trigger part with a bit of nesting material that doesn’t interfere with the tripping mechanism. Scatter some of the nest material on ground in front of box and stick a strand in the hole. (Note: I have found that if I disturb the nest too much, it can spook the HOSP.)

- Fake or Real Eggs as lures: Add real or plastic HOSP egg on top of nesting material, where they can see it.

- Save HOSP eggs (in the refrigerator) and use them as lures in boxes where you want to trap.

- Put one or two fake plastic eggs in the box. This works especially well if you can put a small amount of nest material on the trip “V” of the Van Ert trap, and put the egg on top of the nesting material. You can also glue the nest material with craft egg on top of it directly onto the trip “V.” This both disguises the trip mechanism and makes for almost certain capture when they try to wrestle that alien egg out of the box.

- Fake plastic eggs can be purchased at Michael’s stores, usually near the artificial flower section. Use a spotted egg that looks like a HOSP egg- not a white egg which may attract Tree Swallows.

- Note: Paula Ziebarth even saw a HOSP that had been trapped inside a box with a Van Ert trap pushing the little craft egg out through the breathing hole in the trap.

- Fake or Real Eggs as lures: Add real or plastic HOSP egg on top of nesting material, where they can see it.

- Avoid making eye contact with HOSP when approaching box to set trap. Hide thetrap from his view. Set it quickly and walk away, ignoring him entire time.

- Set an old hinged compact make-up mirror on box floor so he will see himself with trap set, and in he goes.

- Put a fake bird in the box so the HOSP will try to go in and attack it.

- If you have an especially roomy nestbox and male HOSP is dancing around and not setting off the trap, place a dispatched male HOSP in back corner and prop him up outside of trap mechanism zone. You will catch male quickly.

- Temporarily disable the trap (use a paper clip or wire to keep it from tipping) until they become accustomed to it, and then remove the wire. If you are using a Van Ert, put it in upside down for a day or so, so they get used to stepping on the trigger.

- If a HOSP has been trapped in a box and escaped (or even beforehand), tack a fake Black Paper Van Ert inside the nestbox after removing the HOSP nest. You can make one from felt paper used under roofing shingles. This gets them used to a black object under the entrance hole, and then you can catch them more quickly with a real trap. (Keith Kridler)