Content: Species, Interesting Facts, Identification, Distribution, Migration, Diet, Nesting Behavior, Nestboxes, Monitoring, Nesting Timetable, More Info. Also see photos of nests, eggs, and young.

Species: European (Common) Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) or EUST. There are 11 subspecies in Europe and Asia. The species originally released in the U.S. was probably Sturnus vulgaris vulgaris. NOTE: Starlings are non-native invasive species and are not protected by The Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which means that U.S. federal law allows humane destruction of adults, nests, eggs, and young. You should never allow a starling to use a nestbox, as they will aggressively evict other native birds and may attack their eggs and young.

Interesting facts about starlings:

- Both males and females can mimic human speech. (Some people keep starlings as pets). Some starlings also imitate the song of many other birds like the Eastern Wood-Pewee, Meadowlark, Northern Bobwhite and House Sparrow, along with Blue Jays, Red-Tailed Hawks and Cedar Waxwings. Vocalizations inside the nestbox during nest building can be lengthy and quite varied.

- An estimated 1/3 to 1/2 of returning females nest in the same box or area in consecutive years. That is why it’s even more important not to let them nest in the first place.

- A starling couple can build a nest in 1-3 days. Both sexes incubate.

- A migrating flock can number 100,000 birds. They roost communally in flocks that may contain as many as a million birds. Watch this amazing video of a swarming flock of starlings that appear to be feeding.

- Each year, starlings cause an estimated $800 million in damages to agricultural crops (Pimental et al, 2000)

- About 15-33% of first broods are parasitized (via egg dumping) by other starlings.

- Starlings have an unusual bill that springs open to grip prey or pry plants apart.

- Starlings only molt once a year (after breeding) but the spots that show up in the winter wear off by the spring, making them look glossy black.

- In Starlings, the length of the intestinal tract actually varies depending on the season. It is shorter in the summertime (when birds are mainly eating protein-rich) insect foods and larger in wintertime when they are mainly eating seeds, which are rich in carbohydrates. (Source: Analysis of Vertebrate Structure, Hildebrand and Goslow)

Adult starlings are about the size of a chunky Robin. They have glossy black plumage with an irridescent green/purple sheen, a SHORT, squared tail (vs. the long tail of a grackle) and a triangular shape in flight, black eyes (Common Blackbirds have a yellow eye ring), and a long pointy, bill (unlike North American blackbirds) that is yellow during breeding season (January to June) and dark at other times. Legs are pinkish-red. After the first molt, juveniles have grayish brown plumage with lots of white spots (see photo on left) on their head and breast, and they also have a brownish/blackish bill – they almost look like a different kind of bird. It is hard to tell sexes apart. They waddle (vs. hop). Their flight is direct and fast, unlike the rising and falling flight of many blackbirds.

Distribution: After a number of misguided attempts to introduce starlings to North America, perhaps 60-100 starlings were released into Central Park, in New York City, in 1890 and 1891, by an acclimatization society headed by Eugene Schieffelin. Their goal was to introduce all birds mentioned in Shakespeare’s works. The entire North American population, now numbering more than 200,000,000, descended from these birds. By the late 1940s (see map), starlings had been seen in nearly all of the U.S. and Canadian provinces. Their population increased from 1966-1976, but seems to have stabilized since, perhaps due to limited nesting sites. They are found as far north as Alaska and the southern half of Canada, down into northern Mexico. BBS Map

Starlings are often found where ever there is food, nest sites and water – typically around cities and towns, and in agricultural areas. The only places they do not frequent are large expanses of woods, arid chaparral and deserts.

They sometimes flock with other birds like grackles, Red-winged blackbirds, and Brown-headed Cowbirds and may feed with rock Doves, House Sparrows and Common Crows.

Migration: Some starlings migrate, others don’t. Migration also varies by location – they tend to be least partly migratory in the middle Atlantic states, and mostly migratory in the Midwest and Great Lakes regions. Breeding adults south of 40° latitude generally stay put.

Diet: Starlings are adaptable. They are bold and aggressive scavengers of almost anything, including fruit (especially strawberries, blueberries, grapes, tomatoes, peaches, figs, apples, and cherries), grains (e.g., livestock feed), certain seeds, and insects, worms, grubs, millipedes and spiders, and occasionally lizards, frogs and snails. Unlike House Sparrows, 44-97% of their diet is animal matter, depending on the time of year. They are usually seen foraging on open mowed lawns, pastures etc. Starlings seem to have a decent sense of smell – at least they are attracted to peanut butter used in suet.

Nesting Behavior: Starlings are gregarious and will breed in close proximity to other pairs. They are usually monogamous. Fights over breeding sites can result in death. The birds grip each other with their feet while pecking. Nest site fidelity is fairly high, with about one third of returning females coming back to nest in the same box in subsequent years in one study (Kessel, 1957.)

Nestboxes: Starlings can enter a round hole that is 1-5/8″ in diameter, or a slot entrance that is 1-5/16″ tall (some can enter a 1-1/4″ slot). Keith Kridler of TX has found they seem to prefer large (6×6″) man-made boxes mounted on metal/telephone poles, or boxes attached to buildings, 8-40 feet off the ground. They will nest in woodpecker cavities and lower heights if other choices are not available.

Most will not enter a crescent shaped hole 2″ wide x 1-3/16″ tall (often used in Purple Martin houses.) Starlings can not enter a typical bluebird nestbox hole that is 1.5″ wide. However, if the hole is enlarged (e.g., by a squirrel or woodpecker) they may gain access. Some people have reported starlings entering the oval hole of a Peterson bluebird box, and the upsidedown mouse hole of a Gilwood box. Even if they can not enter the box, they may be able to reach inside and attack or remove eggs or nestlings.

Starlings fiercely defend their nest site, and are usually successful at evicting many other species of birds, including woodpeckers, Wood Ducks, Tree Swallows, Bluebirds, Purple Martins and Great Crested Flycatchers, Screech Owls and sometimes Kestrels. In Purple Martin houses, they may remove all the eggs or young of a whole colony and build one nest.

Distance between nests: I have not seen definitive data on how close starlings will nest to each other, except for this: “starling’s nesting territory includes a 10- to 20-inch radius about the nesting hole. Starlings will nest in close proximity to other starlings and other species, although observations indicate that there is a limit to how close they will tolerate neighbors.” (Source: Brina Kessel, 1957)

Monitoring: Starlings may be wary of humans, but they are not sensitive to monitoring or disturbance, and any sensitivity declines with repeated exposure.

- Nest Site Selection: Like bluebirds, starlings are secondary cavity nesters, meaning they do not excavate their own cavities. (However, they may remove rigid Styrofoam insulation or fiberglass insulation to create a nesting space, and old nesting material. Males select the nest site and then females choose a male/site. Resident males start checking out nest sites in late winter, with migratory males are looking by February or March. Starlings will nest in just about any cavity (including cliffs, burrows, rock crevices) and occasionally even in dense vegetation in trees or on the ground. They prefer holes in buildings (barns and open warehouses, signs, and in soffits and attics of houses) and woodpecker holes or natural cavities in trees. Nest sites are generally 10-25 feet (2-60 feet) off the ground, up to 60 feet. Starlings can easily enter a round entrance hole that is 1-5/8″ in diameter. Cavity entrances are, on average, 6.9 x 6.3 cm, 26.4 cm deep, with 149 cm2 of floor area. They will nest in 6″ diameter pipe, and in 8″ hollow block walls (with a cavity that is about 5″x5″.) . They prefer a fairly deep (e.g., 16″) nestbox.

- Nest construction: Males start putting nesting material in the cavity shortly after picking a site. Once they have paired off (late February through March), the couple builds the nest together, usually in the morning and evening. Sometimes the female takes out nesting material brought by the male. They may also remove nesting material (including sawdust or wood chips per Keith Kridler) from a previous nest. A nest can be built in as little as 1-3 days. The nest is bulky and slovenly. The cavity is filled up with grass, weed stems, twigs, corn husks, dried leaves, pine needles, etc, with a depression near the back. Feathers, rootlets, paper, plastics, cloth, string etc. may also be added. The cup lining may include feathers, fine bark, leaves, fine grass etc. Some nests also have fresh green plants (thought to work as fumigants against parasites and pathogens) like yarrow in them. The nest cup is about 7–8 cm in diameter and 5–8 cm deep.

- Egg laying:

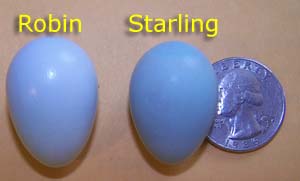

Robin’s egg next to a Starling Egg. Photo by E Zimmerman. Photo looks darker than real life. Starlings usually lay their eggs in synch with neighbors (the first egg within 3-4 days of other starlings nearby.) Dates range from Mar 15 in the southern part of their range to June 15 in the northern part. Eggs are generally laid between 8:00 and 11:00 a.m. Females lay one egg per day, for an average of 4 to 7 eggs total. The slightly glossy eggs are pale bluish- or greenish-white (rare reports of eggs with fine reddish-brown spots), and are slightly smaller and darker than a Robin’s egg.

- Incubation: lasts about 12 days. It begins with the next or next to last (penultimate) egg. Both sexes develop an incubation patch and brood the eggs, but incubation is mostly by the female (70% during the day and all night long). The female may start to brood right after laying the first egg, increasing the amount of time incubating with each subsequent egg. The parents may cover the eggs with some nesting material when leaving the nest.

- Hatching: Hatching occurs 11.5 to 12 days after incubation starts. The hatchlings are nearly naked. The gape is bright orange, and the bill is lemon yellow.

- Development: The nestlings eyes are closed until day 6-7, which is also when contour feathers start to erupt, and brooding ends. Babies can fully thermoregulate by day 13. At this age the babies might try to defecate outside the nest cup or cavity. Before chicks are feathered, adults remove feces. Parents usually remove dead nestlings up to 9 days old. Nests may have tens of thousands of mites in them.

- Fledging: Chicks fledge in 21–23 days. At least one of the parents may feed the fledglings for a day or two afterwards. The young may hang with adults for up to 10-12 days. One study reported fledglings entering another starlings’ nest and stealing food, which resulted in the original brood starving. (Johnson and Cowan 1974)

- Number of broods: There may be second broods (60% of the time if the first is successful, especially common when the first brood is early), south of 48° latitude. If second broods are attempted, nesting activity begins almost immediately, and laying may start within 6-10 days, or even 1-2 days after fledging, but intervals may be much longer (40-44 days). (Kessel 1957). Nest sites may be used for several seasons in a row. New nesting material is usually put on top of an existing nest.

- Roosts: Winter roosts of starlings are noisy and smelly. Fungal spores from excrement under large roosts can threaten human health and safety due to histoplasmosis, a respiratory ailment.

- Longevity: A starling in Germany lived to be 21 years and 4 months old (Feare 1984). 33-77% of birds probably die in their first year.

References and More Information:

- Photos of nests, eggs and young (Sialis.org)

- A. C. Bent 1950. Life histories of North American wagtails, shrikes, vireos, and their allies. U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull. 197: 182–214.

- Cabe, P. R. 1993. European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris). In The Birds of North America, No. 48 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: The American Ornithologists’ Union.

- The Birdhouse Network, Species Account

- University of Florida Extension Service fact sheet

- Economic impact of starlings, USDA/APHIS/WS

- Introduced Species Summary Project

- BBC dawn chorus Sample of the starling’s song

- European Starling videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- The Birder’s Handbook

- Starling Talk – for people who rehab Starlings or keep them as pets which I do not recommend, since they are invasive birds, and wild birds may carry parasites and diseases.

- Starlings – Wildlife Damage Management

- Nest and Egg ID (with links to species biology and photos of nests, eggs and young) for other small cavity nesters

- Hole size entry tests

- Hole size debate

It appears that Starlings are capable of seriously reducing martin populations whenever human beings fail to manage colonies, and since most Purple Martins in North America nest in birdhouses, the future may not be hopeful for this species.

– Dr. Charles R. Brown, American Birds, May 1981, Vol. 35(3):266-268.