A summary of bluebirds and bluebirding through history, including appearances in art, politics and literature; and negative and positive impacts of human activity and conservation pioneers on bluebird populations.

Important Note: This is a work in progress. I am still

adding, checking and verifying some sources, and working on removing plagiarism

and typos:-) It does focus on Eastern Bluebirds. If you have any corrections/additions, please do contact me. Before reading this article, you might want to try

taking the Bluebird

History Quiz. Also see Bluebird Stamps and House Sparrow History.

In 1903, WL Dawson wrote in Birds of Ohio “How the waiting countryside thrills with

joy when Bluebird brings us the first word of returning spring… reflecting heaven from his back and the ground from his breast, he floats between sky and earth like the winged voice of hope.”

Because of their beauty and cheerful song, bluebirds have come to symbolize happiness, love and renewed hope. Although they may overwinter in northern climes, they are often thought of as harbingers of spring, as they actively begin house hunting in February and March.

Throughout history, bluebirds have appeared in stories, poems, art, and films.

One example is the Pima/Cherokee Native American legend: How the Bluebird and Coyote Got Their Color. There are many other examples where bluebirds have appeared in literature, songs, films, and even advertisements.

- 1859: Henry David Thoreau wrote “His soft warble melts the ear, as the snow is melting in the valleys around.”

- 1909: Maurice Maeterlinck published The Blue Bird, a fairy tale about the bluebird of happiness.

- 1934: tenor Jan Peerce made the song Bluebird of Happiness a nationwide hit.

The tune was used in the early 40’s for the Dawn Patrol radio show sponsored by the Pep Boys automotive chain.“And when he sings to you,

Though you’re deep in blue,

You will see a ray of light creep through…

Life is sweet, tender and complete,

when you find the bluebird of happiness.” - 1939: In the movie The Wizard of Oz, Judy Garland sang “Somewhere over the rainbow, bluebirds fly. Birds fly over the rainbow, why, then oh why can’t I.“

- 1941: The White Cliffs of Dover by Nat Burton, music by Walter Kent is one of the most famous of all the World War II era pop classics.

“There’ll be bluebirds over the white cliffs of Dover

Tomorrow, just you wait and see

There’ll be love and laughter and peace ever after

Tomorrow when the world is free.”

The problem with this song, which became a hit in 1942, is that bluebirds are not found in Europe.

- 1955: Marvin Rainwater sang “Gonna Find Me A Bluebird” on Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scout TV Show. It became a runaway hit.

- 1959: A collection of Robert Frost’s poems was published, including The Last Word of a Bluebird.

- 1964: Frank Sinatra recorded I Wish You Love – written by A. A. Beach & C. Trenet.

“I wish you bluebirds in the spring, To give your heart a song to sing, And then a kiss, But more than this, I wish you love!“

Bluebirds have also appeared in paintings, ceramics and jewelry. According to several sources, a bluebird tattoo on a sailor’s chest indicated they had travelled 5,000 sea miles, and a second bluebird indicated 10,000 miles. (Webb, in Tattootime #3, 1988) A Bluebird radio came out in 1934. There was even a car model – the Datsun Bluebird, first manufactured in 1959 (with a Nissan engine–the company name changed to Nissan in 1984.) The biggest “bluebirds” are made by The Bluebird Body Co., founded in 1927, makes buses and motor homes, was reportedly named by Mrs. Luce after she saw a bluebird sitting on a fence during “name” discussions with her husband.

Bluebirds have also appeared in paintings, ceramics and jewelry. According to several sources, a bluebird tattoo on a sailor’s chest indicated they had travelled 5,000 sea miles, and a second bluebird indicated 10,000 miles. (Webb, in Tattootime #3, 1988) A Bluebird radio came out in 1934. There was even a car model – the Datsun Bluebird, first manufactured in 1959 (with a Nissan engine–the company name changed to Nissan in 1984.) The biggest “bluebirds” are made by The Bluebird Body Co., founded in 1927, makes buses and motor homes, was reportedly named by Mrs. Luce after she saw a bluebird sitting on a fence during “name” discussions with her husband.

Like the American Robin, the bluebird, which early on was referred to as the blue robin, blue warbler, or blue redbreast, is a member of the thrush family. There are three species: western, mountain, and eastern. The Eastern Bluebird, the focus of this essay, appears east of the Rockies to the Atlantic coast, from Canada to the Gulf Coast.

Eastern Bluebirds (scientific name: Sialia sialis) are about 5.5″ long. Males have a bright blue back, and a red/rust colored throat and upper breast, and white belly. Females are duller grayish blue with a pale rust throat and breast, white belly, and a white eye ring. Juveniles almost look like another species, with a grayish blue back, white eye ring and spotted breast. Two other birds that are blue – the blue jay and the indigo bunting – are sometimes confused with the bluebird.

Sialia is the Latinized, neuter plural version of the Greek word sialis, a noun meaning a “kind of bird.” The Eastern Bluebird was the first bluebird classified by Carolus Linnaeus

(1707-1778), so he gave it the species name sialis. He placed it in the genus Motocilia, which is now reserved for the wagtails. In 1827, William Swainson decided that the bluebirds needed a genus of their own within the thrush family (Turdidae).

He selected the generic name Sialia which he simply adapted from the species name sialis that Linnaeus had used. Therefore, the scientific name for the Eastern Bluebird is Sialia

sialis (pronounced see-ahl’-ee-ah see’-ahliss). The Western Bluebird and Mountain Bluebird, the two other species within the genus, were named Sialia mexicana and Sialia currucoides (coo-roo-coydees) respectively. Their species names are descriptive of their locations.

See more information common and scientific names and differences between the species.

In the Pleistocene and post-Pleistocene era, the Eastern Bluebird’s range was probably limited to mature pine forests and gaps in deciduous forests. (BNA)

In the Pleistocene and post-Pleistocene era, the Eastern Bluebird’s range was probably limited to mature pine forests and gaps in deciduous forests. (BNA)

Prior to the 1700’s, Native Americans in some areas grew corn, using slash and burn techniques. When the old fields went to weeds, these fields probably provided appealing bluebird habitat. Several Native American stories refer to bluebirds, including the one referenced above. Chimalis (perhaps pronounced SHI-mah-lees) is a native American word for bluebird.

Some 7,000 years ago, Native American tribes in the southwestern parts of North America tied two or three gourd birdhouses together and put them up in dead trees around areas where they dried meat and dumped refuse near villages, to attract cavity nesters like Purple Martins that would feed on the flies and other insects the meat and garbage attracted. Bluebirds will also build nests in a gourd. (Sources: Keith Kridler, Children’s Bluebird Activity Book)

Andre Dion says that the first French settlers in Acadia found the bluebird so pretty that they sent several feathered skins to the French court early in the seventeenth century. (The Return of the Bluebird)

When the first settlers arrived from England, bluebirds were probably as common as the American Robin. A great deal can be learned from early books written by professional and citizen scientists, especially those recording direct observations. They were able to describe bluebird habits in a more natural setting. People were also able to gather more data because of the relative abundance of bluebirds.

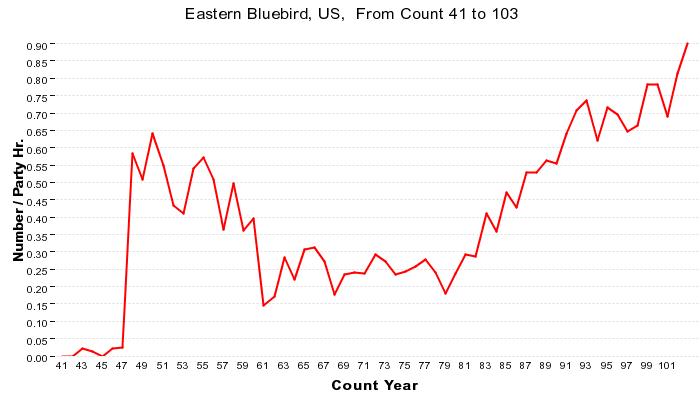

But bluebirds suffered a major decline from the 1920’s to the

1970’s. (See discussion about state listings as a threatened species or species of special concern.) Back in the 1980’s, many people under the age of 40 had

never seen a bluebird. Even today, there are still many people

who have yet to encounter a bluebird.

This essay provides a chronological review of accounts and factors that caused this decline, and also what caused their numbers to increase since the 1970’s. It also dispels the myth that bluebird conservation efforts began in the 1970’s.

With only one exception (weather), changes in bluebird

populations have been directly correlated with the results of human activities.

- Climate plays an important role in short term bluebird population declines – e.g., winter freezes in the South in 1895-96, 1939-40, 1950-51, 1957-58, and severe winters in 1976-77 and again in 1977-78. Bluebirds caught in severe weather without protected roosting locations and sources of liquid water may perish. They may also starve to death if typical winter food sources are gone (e.g., stripped by starlings) or unavailable (e.g., covered by freezing rain/snow.) It’s not just a winter weather issue. Bluebirds that

have migrated North to breed may get caught in severe late spring storms. Hurricanes or severe cold weather in the peak or late part of the breeding season can impact populations. Time to recovery is increased if preexisting populations were already low. Droughts can influence food supply and hatch and survival rates. - Human activities negatively impacting bluebird (and other wildlife) populations include:

- the introduction of invasive species (e.g., House Sparrows, European Starlings),

- changes in land use (e.g., loss of open space, transition of meadows to forest, and forest fragmentation which promotes increases in predator populations like cowbirds and raccoons, natural-fire suppression, lack of forest thinning and clear cutting, snag (standing dead tree) removal

- cars and highways (road kill),

- pesticide use,

- collection (of eggs), hunting (for feathers, still legally practiced by Zunis in New Mexico)

- smokestacks or chimneys (when birds enter and either asphyxiate or die because they can not get out.)

- Mining Claim Markers – these hollow top markers (often made of 4″ PVC pipe) can be scoped out by birds like Mountain Bluebirds and Ash-throated Flycatchers – when they go inside to investigate, they never come out. A single mine marker in Nevada had 42 dead birds inside. (Birdandhike.com)

- Human activities positively impact bluebirds are primarily grass roots efforts to install, manage and monitor nestboxes.

Like most birds, the bluebird population depends in part the weather, predators, and the availability of food. It is also directly affected by the availability of and competition

for nest sites.

Bluebirds are secondary cavity-nesters, meaning their beaks are not strong enough to excavate their own nests. Therefore, they rely on cavities made by others, like woodpeckers, on naturally occurring cavities, or on nestboxes. The availability of nesting sites in the early days was closely tied to land use.

During the days of frontier settlement, the bluebird was one of the species that probably benefited from clearing of eastern forests.

From about 1700-1750, there was an increase in trade for timber (for ships), and potash (ashes from burned trees).

In 1722, Mark Catesby, English artist, traveled to Virginia and published Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. The book contained one plate entitled The Blew Bird. he said “They make their nests in holes of trees, are harmless birds, and resemble our robin-redbreast.” The English robin has a red breast similar to the bluebird.

Beavers were virtually exterminated by trapping which started in Canada in the 1600s. Prior to that, beavers had probably created a lot of bluebird nesting habitat by drowning trees and creating snags.

In colonial times, even before the American Revolution, people used to put up bird houses. These houses were often m ade of clay (fired or bisque) or gourds.

ade of clay (fired or bisque) or gourds.

In the days before pesticides, farmers put up nestboxes around their fields to control pests. Farmers and fruit growers knew that bluebirds were harmless birds that ate a lot of insects. In fact, about 68% of their diet is made up of insects – maybe more during the summer. The fruit they eat during the winter is not the type harvested for human food. Gary Springer noted that when bluebird populations were high, and nesting sites were few (because of removal of trees),

but insects numerous, the bluebird gladly occupied the farmers

nestboxes.

1750-1800: The population of farmers needing land exploded. During this time period, most people raised their own food. Forests were converted into pasture, and fruit tree orchards were planted. Home sites with open areas created ideal bluebird foraging habitat. Bluebirds may also have nested or roosted in recesses in log cabins and farm buildings.

Some early farmers used machines called binders to tie bundles of grain stalks together with twine. A big spool of twine was kept in a large tin container on the side of the binder machine. The twine boxes had a roof and two holes on either side, and were often used as nest sites by bluebirds. (Source: Children’s Bluebird Activity Book. The first binder patent was issued in 1850; the mechanical twine knotter was patented in 1892 in the U.S.)

Some early farmers used machines called binders to tie bundles of grain stalks together with twine. A big spool of twine was kept in a large tin container on the side of the binder machine. The twine boxes had a roof and two holes on either side, and were often used as nest sites by bluebirds. (Source: Children’s Bluebird Activity Book. The first binder patent was issued in 1850; the mechanical twine knotter was patented in 1892 in the U.S.)

Today, nestboxes are primarily used for conservation endeavors or recreational bird watching.

Several early documents mention this practice. Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology (1825?) noted “…few farmers neglect to provide for him, in some suitable place, a snug little summer house, ready fitted and rent-free…And all that he asks is, in

summer a shelter.” In 1842, Henry David Thoreau, the American naturalist, wrote in his diary on September 29th: “Today…the bluebirds, old and young, have revisited their box, as if they would fain repeat the summer without intervention of winter, if Nature would let them.” The Peoples Cyclopedia of Universal Knowledge, published in 1884, noted ” Few

American farmers fail to provide a box for the bluebirds nest.” The 1891 book Our Common Birds and How to Know Them, notes that bluebirds nest “in holes of trees or posts, or in boxes placed for his use in gardens.” A 1913 USDA farmer’s bulletin also contains a reference to erecting nestboxes for pest control.

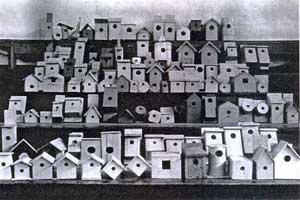

The earliest photographs of nestboxes showed square nestboxes with the entrance hole way up in one top corner. Entrance holes were nearly all square or rectangular because no one had invented a hole saw or a Forschner type bit and the old “Brace and Bit” did not work well on thin lumber. Many builders cut the square hole and then filed it round or carved it with a knife. There were also lots of “key hole” entrance holes with the bottom of the hole flat. (Keith Kridler, Bluebird_L post, 2006)

Early 1800’s: American Ornithology: or the Natural History of the Birds of the United States contains a note about bluebirds, saying “Nothing is more common in Pennsylvania than to see large flocks of these birds in spring and fall….”

By this time, it was probably common for indigenous people like the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes to put up hollowed out gourds for purple martins to ward off other species that pestered their gardens.

1810: The first commercial (horse drawn) railroad, the Leiper Railroad in PA. Railroad tracks with short grass may have created and/or expanded EABL nesting habitat.

1827: William Swainson created a new genus for bluebirds – Sialia (pronounced Cee-AL-ee-a)

1830’s: This was the peak of the “great timber harvest” where forests were clear cut for miles. The harvest reached its peak around the 1830’s, creating a shortage of natural nesting sites. However, wooden fence posts surrounding farms still provided alternatives.

Then humans had a great idea (or so they thought at the time) …let’s import house (English) sparrows to America!

Then humans had a great idea (or so they thought at the time) …let’s import house (English) sparrows to America!

Why? Reasons given for introduction were to establish wildlife familiar to European immigrants, or to control insect infestations. However, in agricultural areas, an average of 60% of the House Sparrows’ diet consists of livestock feed (corn, wheat, oats, etc.), 18% cereals (grains from fields and in storage), 17% weed seeds, and only 4% from insects.

Accounts differ, but it appears that repeated introductions occurred in various parts of the U.S. over ~ a 25 year period. (See http://www.sialis.org/hosphistory.htm for additional information.)

- Initially, eight pairs of House Sparrows (HOSP) were released in Brooklyn, NY in either 1850 or 1851 by a single person/group of New Yorkers – at least one source attributes this to Nicolas Pike, Director of the Brooklyn Institute. Apparently they died before they

could breed. (Source: WB Barrrows) - In 1851, Pike collected more sparrows from Liverpool, England and released 50 in 1852 in Brooklyn NY (in the “Narrows”), while he bred another 50 in Green-Wood Cemetery which were released in 1953 at the Cemetery. (Source: WB Barrows)

- Birds were then released into Central Park (possibly to control worms infesting the trees), Union Square Park , and Madison Square Park.

- In 1854 and 1858, the bird was introduced to Portland Maine.

- In 1858 they were released in Peacedale, RI.

- During the next decade, HOSP were introduced to eight other cities, including release of 1,000 birds in Philadelphia by city officials. By 1870, they were established as far south as Columbia SC and Galveston TX , as far west as Davenport Iowa, and as far north as Montreal Canada.

- Between 1872-1874, the Cincinnati Acclimatization

Society reportedly released 4,000 European songbirds of at least 18 different species, including House Sparrows and starlings. (Note: According to Audubon Action [01/05],”it is commonly believed that a total of about 100 individuals were released into Central Park in New York City in 1890 and 1891. The entire North American population, now numbering more than 200 million and distributed across the continent, is derived from these few birds. Unfortunately, these millions of European Starlings offer intense competition for nesting cavities and have had a detrimental effect on many native cavity-nesting species.”) Large flocks of starlings consume wild foods (e.g., stripping berries from bushes) that may have been utilized by wintering bluebirds. The

gentle bluebirds found it almost impossible to nest successfully in areas where this aggressive bird was abundant. However, unlike the House Sparrow, starlings are unable to enter a properly constructed bluebird nestbox with a 1.5″ hole. - House Sparrows were introduced from Europe to San Francisco and Salt Lake City in 1873-1874.

- Other introductions occurred, and birds were collected and transported to other parts of the country.

- By 1887, some states had already initiated efforts to eradicate HOSPs. The Agriculture Library (1912) contains a chapter entitled How to Destroy English Sparrows. States such as Illinois (1891-1895) and Michigan (1887-1895) established bounty programs.

- In 1903, W.L. Dawson wrote “Without question the most deplorable event in the history of American ornithology was the introduction of the English Sparrow.” (The Birds of Ohio, 1903)

So basically, less than 200 years ago, there were no House Sparrows in North America. Now they are the most abundant songbird on the continent, with an estimated 150 million birds established in all 48 states. This was, and continues to be a problem for bluebirds. HOSP aggressively compete for nest sites. They will destroy eggs, nestlings and adult bluebirds if they can catch them in a nestbox. Also, like other Invasives, they reproduce rapidly, have effective dispersal mechanisms (humans mainly), are rapidly and easily established, and grow rapidly.

Back to agriculture.

1850’s?: Farms in New England were being abandoned and pastures began to revert back to woodlands. A Google search of U.S. patents for birdhouses reveals detailed drawings for early nestbox designs from the 1850’s on.

1863: Dr. R. Michener listed the Eastern Bluebird in an Agricultural Ornithology Report to the Commission for the Year 1863, House of Representatives. He said the bluebird is “resident, very common; rare in winter; insectivorous. This favorite of every household,

the lovely and confiding bluebird, seeks its food on the ground among grass. It seems to prefer coleopterous beetles, but also devours other insects, caterpillars, spiders, &c.,

and sometimes ripe berries. It well repays the use of the box, so often provided for its habitation.”

1865: After the Civil War ended, more settlers began moving westward to the prairies. As cleared areas succeeded back to forest, bluebird numbers may have reverted to pre-settler levels. (Source: Bluebirds in My House)

1870: Another non-native cavity nester, the Eurasian Tree Sparrow (Passer montanus) was introduced to the U.S. 20 birds were released in Lafayette Park, St. Louis MO by a bird dealer who imported them from Germany. For whatever reason (less aggressive, competition with house sparrows), the Eurasian Tree Sparrow has not spread far beyond eastern Missouri, west-central Illinois and southeastern Iowa.

Late 1800s: EABL first appeared in Manitoba. (BNA)

1880’s – 1900: Egg collections was a popular hobby and scientific pursuit. AC Bent noted that during that time period “we always looked for bluebird’s’ nests in natural cavities in apple trees in old orchards, and fully 80% of our nests were found in such situations, though we found some in natural cavities in other trees and in old woodpecker holes. Nesting boxes were not so plentiful in those days as they are today.”

1880s-1920: Domestic animals replaced game as source of meat. Livestock feed attracts HOSP. HOSP thrived in areas occupied by humans, eating grain that was left on the ground, undigested grain in horse manure, and trash.

1884: The Peoples Cyclopedia of Universal Knowledge, Vol.1, referred to the bluebird as “An American bird, which, from the confidence and familiarity it displays in approaching the habitations of men, and from its general manners.. Few American farmers fail to provide a box for the bluebirds nest.”

In another account from that year: “October 23, 1884, Girard Manor, Schuylkill county, Penn’a (sp). Bluebirds very abundant; a flock of about two hundred have every day for the past two weeks been observed distributed over the field….” (Birds of Pennsylvania, 1900?)

1888: The Cartersville Courant-American noted: “The English Sparrow, with its grown and growing progeny, is a conspicuous nuisance. Can there be no way devised to abate him, if not totally, at least partially?” (Sep. 6, 1888, page 5)

1890 (1880 per Scriven?): In March 1890, a New York drug manufacturer named Eugene Schieffelin decided to release all songbirds mentioned in Shakespeare into Central Park. He let loose thrushes, skylarks and European starlings, of which only the starlings survived (NY Times 2006). Dr. Lawrence (Larry) Zeleny said that

prior to the introduction of the House Sparrow and the starling, “…bluebirds had no particular need for human help. Man had done little if anything to interfere with their lifestyle and they were obviously quite capable of coping with their natural enemies – otherwise they would have disappeared long before.” (Source: The Return of the Bluebird, foreword by Zeleny, 1981) Because starlings are so prolific and aggressive, bluebirds found it almost impossible to nest in areas where starlings were abundant. Their introduction

made provision of starling-proof nestboxes even more important.

In the winter and spring of 1894 -1895, the sudden return of cold weather almost wiped out bluebirds in the great lakes and New England.

“Thousands of Bluebirds perished in the storms and bitter cold which lasted for a week or more; their frozen bodies were found everywhere– in barns and other outhouses where the poor things had vainly sought shelter; in the fields and woods and even along the roadsides. In the localities affected they were almost exterminated. To many people it was a sad spring in those regions.” (Source: Birds of America: 1917 and 1936, article by George Gladden) Amos Butler of Indiana wrote in 1898, “”The Bluebirds seem to have been almost exterminated. Few, indeed, returned to their breeding grounds in the north and from many localities none were reported in the spring of 1895.” (Bent, 1949) It was five or ten years before numbers returned to normal. (? “Bluebird Storm” – March 1893 blizzard and sudden temperature drop reduced the population of migrating bluebirds in Wisconsin to near zero? Checking on date – source Sand County Almanac?)

1897: Several years later, John Burroughs wrote: “A few seasons ago I feared the tribe of bluebirds were on the verge of extinction from the enormous number of them that perished from cold and hunger in the South in the winter of 1894. For two summers not a blue wing, not a blue warble. I seemed to miss something kindred and precious from my environment – the visible embodiment of the tender sky and wistful soil. What a loss, I said, to coming generations of dwellers in the country–no bluebird in spring! …But the fear was groundless: the birds are regaining their lost ground; broods of young blue-coats are again seen drifting from stake to stake or from mullen-stalk to mullen-stalk about the fields in summer, and our April air will doubtless again be warmed and thrilled by this lovely harbinger of spring.”

Early 1900s: The EABL expanded its range into the Great Plains grasslands. (BNA)

HOSP populations may have peaked. Later, when automobiles and farm machinery replaced horses and farm animals, the primary source of food for HOSPs was reduced. In the early 1900’s, bluebirds were still a common sight in suburbs and rural areas. (Source: The Birds of Concord, Ludlow Griscom, 1949). However, reliable population data is not really available.

Mature trees were still being harvested for firewood and building material for major Eastern cities. (Source: Bluebirds in My House)

The decline in bluebird populations may have begun after this time, compounded competition from HOSP and other changes:

- Wooden fence posts were being replaced with metal posts

- Field borders and fence rows were cleared to increase cropland acreage

- Dead branches were pruned from decrepit apples trees, cavities filled, or old trees were removed entirely, replaced with new young trees that are regularly pruned and sprayed.

- From 1900-1960’s, old tobacco barns used heaters that killed bluebirds by the thousands, trapping in steel vent pipes. It was verified that in just one season, over 300 dead bluebirds were found in a single heated tobacco barn.

1900: By the late 1800s, hunting and shipment of birds for the commercial market for food, and plumes (to provide feathers to adorn lady’s hats) had taken their toll on many bird species. The Lacey Act was passed on May 25, 1900 to prohibit game taken illegally in one state to be shipped across state boundaries contrary to the laws of the state where taken.

1900:

Around the turn of the 20th century, some observers and scientists were becoming concerned about declining bird populations. Ornithologist Frank M. Chapman, an early officer in the Audubon Society, proposed a new holiday tradition, as a non-violent alternative to the Christmas “Side Hunt,” where teams competed to see who could kill the most animals. On Christmas Day, the first Christmas Bird Census (Now the Christmas Bird Count) was conducted. At the suggestion of ornithologist Frank M. Chapman. 27 participants counted 18,500 individual birds, including eastern and Western Bluebirds. (USFWS)

1904: The book North American Birds Eggs noted that the Eastern Bluebird winters in the southern half of the United States. “These familiar birds build in cavities in trees, usually below 20 feet from the ground, crevices among ledges, bird boxes and in any suitable nook they may discover about buildings, providing that English Sparrows do not molest them. They raise several broods a year, commencing in April when they lay from three to six pale bluish white eggs (rarely pure white)….. The cavities of their nesting sites are lined with grasses and feathers usually, although I have found the eggs on the unlined bottom of cavities in trees.…The Western Bluebird is as common and familiar in its range

as the common Bluebird is in the east. (Source: North American Birds Eggs, by Chester A. Reed)

1905: National Association of Audubon Societies founded by William Dutcher, an offer of the American Ornithologist’s Union. (Rosenthal)

1906: During a severe winter in Central Mississippi, much of the normal breeding population froze to death or died of hunger or thirst. (AC Bent)

1911-1912: Jack Frost struck again, with a very cold winter in the Southeastern states, but this was more local and recovery was quick. Thomas Edgar Musselman estimated that fifteen hundred to two thousand eggs were frozen in his area in April. (AC Bent). In the spring of 1912, hundreds of bluebirds starved to death in Illinois alone (Dodson)

1913:

By the late 1800s, the hunting and shipment of birds for the commercial market (to embellish the platters of elegant restaurants) and the plume trade (to provide feathers to adorn lady’s fancy hats) had taken their toll on many bird species.

The Lacey Act (passed on May 25, 1900) prohibited game taken illegally in one state to be shipped across state boundaries contrary to the laws of the state where taken.

1913: The USDA Farmers Bulletin #513, Fifty Common Birds of Farm and

1913: The USDA Farmers Bulletin #513, Fifty Common Birds of Farm and

Orchard, states: “The bluebird is one of the most familiar tenants of the farm and dooryard. Its favorite nesting sites are crannies in the farm buildings or boxes made for its use or ? natural cavities in old apple trees. For rent the bird pays amply by destroying insects, and takes no toll from the farms crop. The largest items of insect food are grasshoppers first and beetles next, while caterpillars stand third. The vegetable food consists chiefly of fruit pulp, only an insignificant portion are from cultivated varieties.“

1914: By implementing the assembly line, Henry Ford increased the production of automobiles and made them less expensive. Thus they were accessible to more Americans. More cars, more roads, and eventually highways, meant more road kill of birds. See Your Environmental Tire Tread.

1915: Professor Beal reported on results of examining the stomachs of 855 Eastern Bluebirds in a USDA Bulletin (#117, Food of the robins and bluebirds of the U.S.) It would probably be unthinkable today to sacrifice that number of bluebirds today for a scientific study.

1917: Individuals continued to encourage bluebird nestings. Neltje Blanchan wrote: “Now is the time to have ready on top of the grape arbor, or under the eaves of the barn, or nailed up in the apple tree, or set up on poles, the little one-roomed houses that bluebirds are only too happy to occupy. … Sparrows will fight for the boxes, it is true, but if there are plenty to let, and the sparrows are persistently driven off, the bluebirds, which are a little larger though far less bold, quickly take possession. …As two or even three broods of bluebirds may be raised in a box each spring, and as insects are their most approved baby food, it is certainly to our interest to set up nurseries for them near our homes. But when people are not thoughtful enough to provide them before the first of March, the bluebirds hunt for a cavity in a fence rail, or a hole in some old tree, preferably in the orchard, shortly after their arrival, and proceed to line it with grass.” (Birds Worth Knowing, 1917)

1918: Larry Zeleny began to be concerned with the plight of the bluebird, when he found that without constant vigilance and interference on his part, House Sparrows nearly always evicted bluebirds from the nestboxes he had built for them. He wondered how bluebirds could possibly survive as a species without human help. And at that time starlings were unknown in his home state of Minnesota. (Source: The Return of the Bluebird, foreword by Zeleny, 1981)

1918: The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (enacted in 1913 but under court challenge since then) was ratified by Congress, to end to commercial trade in birds and their feathers that, by the early years of the 20th century, had wreaked havoc on the populations of many native bird species. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act decreed that all migratory birds and their parts (including eggs, nests, and feathers) were fully protected. (See Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 under Title 50 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Section 10.13) (USFWS) House Sparrows and starlings are not currently protected under this law, as they are non-native birds that are considered pest species (primarily for agricultural and health reasons).

1919: The bluebird “makes its nest in the hole of a tree or in the box that is so commonly provided for its use by the friendly farmer.”

Prior to 1921??:

Larry Zeleny purchased a deluxe, six-dollar sparrow trap from Joseph H. Dodson after a House Sparrow occupied a bluebird nestbox he put up.

1920’s: A book noted that starlings could be excluded from bluebird nestboxes if the entrance hole was precisely cut to 1.5″ square. (Keith Kridler – book source?)

EABL first appear in Saskatchewan. (BNA)

1926: Thomas E. Musselman of Quincy Illinois is generally credited with originating the bluebird conservation movement that extended beyond local boundaries. He also came up with the concept of a “bluebird trail.” He designed his own boxes with removable tops, and started putting them up along country roads, eventually expanding to 1,000 boxes. He experimented with boxes of different depths, floor sizes, roof styles, boxes made from gourds, logs and cylinders, square holes, “mouse holes” (oval top with flat bottom – upright and inverted), rectangular slots, round and oval holes of various sizes. (Bluebird Monitors Guide, p. 94) He also experimented with ventilation, drainage, floor dimensions and cavity depth in boxes. Musselman was a scientist, businessman, college teacher, family man, naturalist, bird bander, and organizer. T.E. Musselman was born 04/28/87, died at the age of 89. (Bluebird Trails, Coeur d’Alene National Audubon Society, Vol.14, Issue 2., birth date correction from Gail Harmeyer)

1926: The chain saw was patented in 1926, and mass production of a gasoline-powered chain saw began in 1929. Early models were very heavy, but after WWII chain saws that one person could handle became available. They made cutting down trees (including snags) easier, which could have impacted nesting sites (natural and woodpecker-excavated cavities). (Tekiela and Wikipedia.org)

1927: The Eastern Bluebird was named state bird by Missouri.

1928: M.P. Skinner reported that during cold spells, he found as many as 70 bluebirds gathered together in the Carolinas. (AC Bent)

1928: M.P. Skinner reported that during cold spells, he found as many as 70 bluebirds gathered together in the Carolinas. (AC Bent)

Joseph H. Dodson published a pamphlet/catalog entitled Your Bird Friends and How to Win Them that pictured multi-compartment birdhouses he indicated were used by bluebirds for successive broods. He also sold a sparrow trap that was used by Zeleny.

Date? c1931? “….Frank M. Chapman, one of America’s leading ornithologists, predicted that the starling, which in America was then confined to a small area within about 100 miles of New York City, would eventually become a serious threat to the bluebird.” (Source: The Return of the Bluebird, 1981)

1931: The Mountain Bluebird was adopted as the state bird for Idaho by the legislature. It was selected through a campaign held in 1929. Idaho’s women’s clubs supported the tanager, but more than half of school children favored the Mountain Bluebird (May 6, 1929 issue of the Idaho Daily Statesman)

1934: Musselman, who continued to be concerned about bluebird population decline, wrote an article in Bird Lore calling on others to establish trails. There was widespread public participation. In 1934, he set out 25 nestboxes along back country roads and monitored them closely. Later on, he had more than 100 boxes over 43 miles. He continued lecturing and corresponding with others interested in bluebirds, such as William Duncan of Kentucky

Duncan, who corresponded with Musselman from 1930 until Musselman died in 1976, designed another nestbox style and put up hundreds of boxes in Jefferson Country, KY. His great granddaughter, Stacey Jansen, shared that Duncan his own newsletter together in his basement office with the help of his wife Azalea Duncan. In addition, he installed hundreds of nesting boxes—his own design—across Kentucky.

1936: Amelia Laskey, a citizen scientist, started a trail in Percy Warner Park, Nashville, Tennessee.

1937: Robie W. Tufts wrote to A.C. Bent that in October a flock containing “some hundreds” of bluebirds was observed in Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, where they were normally scarce.

1938: “One of the most obscure yet most ambitious efforts in the history of bluebird conservation was the development of the National Bluebird Trail. It started with the Junior Audubon Club of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, organized by Mrs. Oscar Findley in 1938. Under her guidance, the Club developed a successful local bluebird trail. Soon thereafter, Mrs. Erie R. Jackson of the Better Garden Club of Kirkwood, Missouri secured permission from the Missouri Highway Department to place nestboxes along Missouri highways. Her club adopted this plan as their project early in 1942 and began developing a state-wide trail. Later that year, the trail was taken over by the State Board of Federated Garden Clubs of Missouri and the Missouri Bluebird Trail consisting of 2,680 nestboxes was officially dedicated. Within three years, garden clubs in 23 states from coast to coast had joined the effort. On May 9, 1945 the National Bluebird Trail was formally dedicated in Springfield, Missouri. By 1946, a total of 6,728 nestboxes had been erected. Unfortunately interest in maintaining this mammoth project soon waned, probably because of lack of strong central leadership. The trail began to disintegrate and before long ceased to exist as an entity. In various areas, segments of it were continued, and the project no doubt served a useful purpose in arousing the interest of many people who have continued to help the bluebirds in local areas.” (by Larry Zeleny, forward to Andre Dion’s The Return of the Bluebird, 1981)

the Junior Audubon Club of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, organized by Mrs. Oscar Findley in 1938. Under her guidance, the Club developed a successful local bluebird trail. Soon thereafter, Mrs. Erie R. Jackson of the Better Garden Club of Kirkwood, Missouri secured permission from the Missouri Highway Department to place nestboxes along Missouri highways. Her club adopted this plan as their project early in 1942 and began developing a state-wide trail. Later that year, the trail was taken over by the State Board of Federated Garden Clubs of Missouri and the Missouri Bluebird Trail consisting of 2,680 nestboxes was officially dedicated. Within three years, garden clubs in 23 states from coast to coast had joined the effort. On May 9, 1945 the National Bluebird Trail was formally dedicated in Springfield, Missouri. By 1946, a total of 6,728 nestboxes had been erected. Unfortunately interest in maintaining this mammoth project soon waned, probably because of lack of strong central leadership. The trail began to disintegrate and before long ceased to exist as an entity. In various areas, segments of it were continued, and the project no doubt served a useful purpose in arousing the interest of many people who have continued to help the bluebirds in local areas.” (by Larry Zeleny, forward to Andre Dion’s The Return of the Bluebird, 1981)

Late 1930’s: A very aggressive red fire ant (Solenopsis invicta Buren) was introduced into the U.S. Four species of fire ants are found within the contiguous southeastern United States. The tropical fire ant, Solenopsis geminata Fabricius, and the southern fire ant, S. xyloni McCook, are considered “native.” A black ant (Solenopsis richteri Forel) was introduced in 1913 from South America at the port of Mobile Alabama, probably in soil used as ballast in cargo ships. (USDA)

Since its introduction, the red imported fire ant has spread quickly, probably through landscaping materials (sod and woody ornamental plants.) By 1953, imported red fire ants were found in 10 states. Today, the red imported fire ant has spread throughout the southeastern United States and Puerto Rico.

It now covers more than 300 million acres in the USA. It has spread from the East Coast to the Pacific coast and is traveling north in California. It has replaced the two native species and is displacing the black imported fire ant. Currently, S. richteri is found only in extreme northeast Mississippi, northwest Alabama and a few southern counties in Tennessee. (USDA, Kridler)

Imported red fire ants are now a major problem on a bluebird trail. A single queen fire ant will lay around 225,000 eggs a year and has a life span of three years. Each mound may contain as many as 100 laying queens. Attracted by old nesting material, they may invade a nestbox with a female incubating eggs and force the female to flee or be eaten alive. They cannot break into the eggs, but often attack the young birds as they just begin breaking out of the shell. They will kill the young bird while in the shell and clean out the entire bird through a tiny hole. The ants can strip a baby bluebird down to a skeleton in a matter of days. (Keith Kridler)

In the later half of the 1900’s, there was also:

- Continual increase in pesticide use. Nestboxes that farmers had put up around fields could have increased bluebird exposure to pesticides. Pesticides have been used since 500 BC., but it was not until the 1900’s that concentrated chemical formulations gained widespread use??.

- Urban Sprawl: loss of open space, and forest fragmentation, and loss of old growth forests

- Trimming of dead snags. In residential areas, people generally don’t want standing dead trees in their yard.

- Cities, residential areas, industrial parks and large commercial farms replacing natural habitat and small family farms.

- Fewer grass pastures and animal manure in which insects breed.

1940’s: Starlings reached California. In Bermuda, a cedar scale endemic in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s destroyed over 90% of their cedar forest. Many of the dead trees were removed for aesthetics and reforestation. Up until that time, holes in cedar trunks had been the primary nest site for bluebirds. (Source: Bermuda Bluebird Society)

1940: More than 50% of the bluebird population in Illinois died during ice storms (Musselman 1941 per BNA).

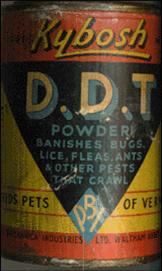

1942: DDT was first used in U.S. It was often sprayed from planes and fire hoses.

1942: DDT was first used in U.S. It was often sprayed from planes and fire hoses.

1946: Walt Disney produced a movie (their first big live-action picture) called “Song of the South.” One memorable scene has Uncle Remus walking through a pastoral backdrop singing what became an Academy Award winning song, “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah”

“Mister bluebird’s on my shoulder

It’s the truth, it’s actual

Everything is satisfactual”

while a friendly cartoon bluebird flitted around. Ironically, by this time bluebird populations were already dwindling. The film was reshown in theatres in 1956, 1972, 1980 and 1986. As of 2007, Disney has not released it on video, probably due to concern about black stereotypes.

Late 1940s-50s: Pesticide use increased, probably peaking in 1959. DDT was used in massive quantities. It took years for insect populations to recover. Farmers said could grow peaches for years afterwards without using pesticides. (Source: Gary Springer.) Note: DDT was actually first synthesized in 1874. Its effectiveness as an insecticide, however, was only discovered in 1939. Shortly thereafter, particularly during World War II, the U.S. began producing large quantities of DDT for control of vector-borne diseases such as typhus and malaria.

After 1945, agricultural and commercial usage of DDT became widespread in the U.S. The early popularity of DDT, a member of the chlorinated hydrocarbon group, was due to its reasonable cost, effectiveness, persistence, and versatility. Impacted insect populations and eggs. On the other hand, HOSP didn’t need insects. In the 40’s, flocks HOSP described as in the hundreds or even thousands created a nuisance in barns and outbuildings.

1940s-50s – WWII ended. Soldiers returned to the U.S., families grew, small woodlots were cut down, and urbanization increased.

1940s-50s – WWII ended. Soldiers returned to the U.S., families grew, small woodlots were cut down, and urbanization increased.

1948: Cat litter became commercially available, allowing people to keep cats indoors. (As of 2007, an estimated 65% of domestic cats are allowed outdoors, along with feral cats.)

1949: Ornithologist Arthur C. Bent’s Life Histories of North American Thrushes, Kinglets, and Their Allies, was published, with wonderful and poetic accounts of bluebird history and studies. In it, he notes there has been “an immense increase in the number of bird boxes put up by appreciative bird-lovers and by agriculturists who are now well aware of the economic value of the birds.”

1950: Some sources (reliability?) claim the CIA approved a mind control experiment called “Project BLUEBIRD” on April 20, 1950. This project, renamed “ARTICHOKE” in 1951, and “MKULTRA” in 1953, supposedly dealt with creating amnesia and use of hypnotic couriers, ala The Manchurian Candidate. (BLUEBIRD, Deliberate Creation of Multiple Personality by Psychiatrist, by Colin A. Ross MD)

An incense formula for the Navajo Shooting Chant and Hail Chants include feathers from brightly colored birds, including bluebird. (Source: Navajos, Gods, Tom-toms, by S.H. Babington, 1950). Also see information on Zuni use of bluebird feathers.

1950’s: William Duncan started a conservation newsletter, which was eventually distributed to 1,500 people. (Source, Foreword to The Return of the Bluebird)

1950’s-60s: Cats became more popular. Outdoor cats probably kill at between 14 and 1000 wild animals per year, about 20% of which are birds. Local extinction can result when existing bird populations are already very small.

1951: Philip Hummel in Wisconsin started a bluebird trail on his farm. It attracted the attention of the Wisconsin Society of Ornithology, which urged 4H clubs to establish trails as a club project, and published a 4-H bulletin called Bluebird Trails Guide.

1955: Charles Ellis, a salt-of-the-earth rancher, set out his first homemade Mountain Bluebird box on his farm near Red Deer Alberta, at what later became the Ellis Bird Farm Ltd. Eventually he had over 300 boxes, and the highest nesting density of bluebirds ever recorded. (Ellis Bird Farm History) His success was attributed to his efforts to virtually eliminate HOSP and starlings from his property. (Return of the Bluebird – which has the year as 1956.)

1957: Operation Bluebird was started by William Highhouse in Pennsylvania.

1957: The bluebird population in Illinois, which was estimated at 460,000 in 1909, was down to 220,000 by 1957. (The Birds of Illinois, H. David Bohlen, 1989)

1958-60: Severe winters occurred. Trees and shrubs were covered with freezing rain, ice or snow, making berries unavailable. “Frozen bodies were found throughout the bluebird’s main wintering range, with estimates that up to 50 percent of the population had perished.” (Source: Bluebirds in My House)

1959: John and Nora Lane organized a Boys Club in Manitoba called the Brandon Junior Birders. They built boxes and set them up along roadsides. The word spread across the provinces. Eventually 7,000 boxes were installed, fledging an estimated 5,000 bluebirds (mostly Mountain Bluebirds) each year.

1960s: EABL expanded range into Chiricahua Mountains of Arizona (Ligon, 1969, BNA)

1962: Raleigh Stotz of Michigan with the Grand Rapids Audubon Club started a “Bluebirds Unlimited” project, an experimental trail to study predator control, etc. He distributed educational material and sold 15,000 nestboxes virtually at cost.

1962: Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published. She said “Who has decided – who has the right to decide – for the countless regions of people who were not consulted that the supreme value is a world without insects, even though it be also a world ungraced by the curving wing of a bird in flight?” “Over increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song.” The book stimulated the environmental movement.

1962: Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published. She said “Who has decided – who has the right to decide – for the countless regions of people who were not consulted that the supreme value is a world without insects, even though it be also a world ungraced by the curving wing of a bird in flight?” “Over increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song.” The book stimulated the environmental movement.

1963: The bluebird population may have reached its lowest point ever. (Bluebirds in My House)

An episode (#312) on the popular TV series Lassie aired on March 24, 1963, called “Project Bluebird.” In it, Timmy begins building birdhouses when he discovers that the bluebird population is declining due to lack of nesting places. His plan succeeds—until starlings invade the neighborhood, forcing the local farmers to use desperate measures: dynamite! (The Unofficial Lassie Website)

1964: Ralph Bell of Pennsylvania, a poultry farmer, started a trail on utility poles (with permission) along country roads where he delivered eggs. He put up about 200 boxes, with as many as 800 bluebirds fledging each year.

1964: The National Association for the Protection and Propagation of the Purple Martins and Bluebirds of America (NAPPPMBA) was organized by M.D. Anglin, an Arkansas attorney, and Charles C. Butler, a Kansas grocer. The organization issued monthly newsletters to its 400 members and distributed approximately at cost about 7,000 copies of bluebird nestbox plans and instructions and 4,000 copies of a 16-page booklet Bluebirds for Posterity written by Zeleny.

1966: The Breeding Bird Survey began to systematically monitor bird populations in North America.

1967: After his retirement as an agricultural biochemist, Zeleny got permission to put up 13 nestboxes for bluebird research at the Beltsville Agricultural Center where he had worked. He also bought 144 nestboxes and asked that they be placed around the state’s parks.

The parks project was aborted due to human vandalism. (Source: Dr. Lawrence Zeleny, An Odyssey of Love)

1967: Edwin T. McKnight of Bethesda, Maryland began operating bluebird trails in both Maryland and Virginia, the most successful of which was in Stafford County, Virginia.

1967: The Audubon Naturalist Society of the Central Atlantic States launched a bluebird project, and a similar project was begun in 1969 by the Maryland Ornithological Society. These two projects soon became integrated. Some 75 collaborators participated in the work. By the end of 1978, about 3,100 nestboxes were being maintained. An estimated 28,600 Eastern Bluebirds had fledged from the boxes during the 12 years of the project. (Forward to The Return of the Bluebird)

1967: The Nevada state legislature named the Mountain Bluebird as the official state bird in 1967. Clark County Assemblyman Stan Irwin introduced the bill NRS 235.060, which was signed by the governor on April 4th.

1968:

Richard M. Tuttle, a junior high school teacher in Delaware County, Ohio started his own bluebird trail in 1968. Inspired by its success, he started teaching students how to construct and mount their own nestboxes in a proper habitat. Some of these students became sufficiently interested to develop their own bluebird trails. (Forward to The Return of the Bluebird)

1968: Jess and Elva Brinkerhoff started a small bluebird trail in south-central Washington, which later expanded into a trail of more than 800 nestboxes scattered covering about 150 square miles. Almost all of the boxes were used every year by Mountain Bluebirds and some Western Bluebirds. There were very few bluebirds in the area before the trail was started. (Forward to The Return of the Bluebird). More on Bickleton and the Brinkerhoffs.

In 1968, Dick Tuttle put up 22 nestboxes for bluebirds in Delaware County in Ohio. Since then (as of 2006), he has raised 8,235 Eastern Bluebirds, 16,686 Tree Swallows, 5,514 House Wrens, 508 Carolina Chickadees, 47 Tufted Titmice, and monitors more than 360 nestboxes (including Kestrels, Wood Ducks, owls) weekly. (Keith Kridler)

1969: NAPPPMBA was dissolved in 1969 and its work passed into the hands of the Griggsville Wild Bird Society (now The Nature Society) which published Purple Martin Capital News (now Nature Society News). This paper published a monthly “Bluebird Trail” column for many years. The column was written by T.E. Musselman prior to 1969, by Larry Zeleny from 1969 to 1981, then by Ben Pinkowksi, Harry Krueger, Marcy Hoepfnar, Steve Garr, and others. This column created widespread interest in bluebird conservation throughout much of the United States and Canada.

1969: Hubert W. Prescott of Portland, Oregon had been concerned about the dwindling population of the Western Bluebird, particularly in the region of Oregon’s fertile Willamette Valley. He began a serious study of the problem and concluded that one of the principal troubles was that, in the development of the Valley’s land for intensive agriculture, the natural cavities needed by the bluebirds for nesting had been mostly destroyed.

1969: A New York newspaper noted that “Bluebird don’t have much to sing about these days…they’re disappearing so rapidly almost everywhere east of the Rockies that they may become extinct before the end of the century.” (Ocala Star Banner, January 27, 1969, page 2.)

1970s: EABL first appeared in SE Alberta during the 1970s and 80s. (BNA)

1970: Ralph M.J. Shook of Godfrey, IL, remembering the abundance of bluebirds in his native Calhoun County during his boyhood, was appalled at how scarce they had become by 1970. Determined to do whatever he could to remedy the situation, he began building nestboxes which he then set out in rural areas. Some he gave away to others who agreed to mount them in proper locations. By 1973 ,nearly 500 of his nestboxes had been set out, roughly half of which were occupied by bluebirds, and the badly depleted bluebird population of Illinois’ Calhoun County was making a substantial comeback.

During the same period, Thomas Beasley of Oakland City operated what was perhaps the most extensive and successful bluebird trail in the State of Indiana (source? confirmation?).

By this time, Lorne Scott of Saskatchewan was monitoring 2,000 nestboxes virtually single-handedly. Bird banders Mary and Dr. Stuart Houston also organized part of what is now the Canadian Prairie Bluebird Trail. (The Return of the Bluebird)

Eastern Bluebird designated state bird of NY on May 18, 1970 by Governor Rockefeller (Chapter 824, section 78 of the State Laws of 1970). One delegate objected, stating “I think this is a bit premature. After all, who has ever seen a bluebird, except perhaps on the cover of a greeting card?”

Ira L. Campbell of Timberville started setting out nestboxes in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, where starlings had taken over most natural tree cavities. Within a few years, he was maintaining more than 100 boxes along 32 miles of country roads in what became the Shenandoah Bluebird Trail.

1971: A bluebird trail was initiated in Alberta by Joy Finlay of Edmonton.

1971:Reuel Broyles of Springfield, Missouri starting making thousands of nestboxes and giving them to people and organizations in Missouri. He also maintained his own bluebird trail.

1972: DDT was banned by EPA, canceling nearly all remaining Federal registrations of DDT products. Public health, quarantine, and a few minor crop uses were excepted, as well as export of the material. (Note: DDT is still used in tropical regions to control malaria, which the WHO estimates kills one child under the age of 5 every 30 seconds.) We usually associate pesticide use with agriculture; but actually use per acre on homeowner lawns is higher on average.

1973: The Endangered Species Act was passed. Eventually many states passed similar laws. These laws provide limited protection, usually depending on the funding source for

projects. A lot of people get confused about the status (historical and current) of bluebirds because of discussions about declining populations. However, to my knowledge, bluebirds have never been placed on any federal lists of endangered or threatened

species. They are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. They are not protected under CITES (?) or the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Note that not all listings are by regulatory agencies (e.g., Audubon.)

- Eastern Bluebird:

- At one point, the Eastern Bluebird was listed as a species of special concern in the State of New York (removal was proposed in 1987 as it was faring better ).

- According to the USDA Forest Service, it was listed as of special concern in Montana and a “watch” species in North Dakota.

- In a 1979 compilation of state lists, the Eastern Bluebird was listed as rare and/or endangered in Connecticut (1976), existing in limited numbers in Massachusetts, and uncommon and declining in New Hampshire.

- It was listed in the South Dakota Natural Heritage Database as a species monitored by the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish, and Parks.

- In Canada, the Eastern Bluebird is? listed as vulnerable in Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan.

- It was on the Audubon Society’s (non-regulatory) Blue List in 1972, from 1978 to 1982, and of Special Concern in 1986.

- Mountain Bluebird:

- The Mountain Bluebird was listed by Colorado, with an “undetermined” status. (Atwood, 1994)

- Appeared on the National Audubon Society’s Blue List in 1971, 1972 and 1974. (Power)

- Western Bluebird:

- listed as a candidate species in Washington (Atwood, 1994)

- listed as a sensitive (vulnerable) species in Oregon (Atwood, 1994)

- listed as sensitive (declining population due to limited range or habitat) in Utah. (Atwood, 1994).

- It was also on Audubon Society’s (non-regulatory) Blue List in 1972 and was listed again from 1978 to 1981, and considered of special concern in 1982 and of local concern in 1986. (Tate, 1986).

- Listed as high concern by New Mexico Partners in Flight (Hall, 1997)

- Proposed as species of “special concern” in British Columbia (Weber 1980.)

- All 3 species:

- On the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species – 2008 status “Least Concern” (ver.3.1, as of 02/19/2010)

1973: The Camp Fire Girls began Project Save the Bluebirds. Projects like this instilled a greater love and respect for living things and an understanding of the serious problems faced by wildlife. The future of conservation efforts lies with them. Since then, various Boy Scout, Girl Scout, and 4-H Clubs have also organized bluebird projects. Unfortunately, the boxes put up by these groups are not always properly monitored or maintained.

1973: Hubert W. Prescott initiated bluebird trails in three separate areas of the Willamette Valley. The project was generally successful, and was expanded with support from the Portland Audubon Society.

1973: Jack R. Finch of Bailey, North Carolina organized the non-profit bluebird conservation corporation “Homes for Bluebirds”, Inc. Through his organization, Finch began building and setting out nestboxes in carefully selected locations throughout much of North and South Carolina. These included nestboxes of several different original designs.

1973: Harold Pinel of Calgary started a bluebird trail.

1974: Ellis Porter, the game warden of Aberdeen Proving Ground set up a tail on their 80,000 acres in Maryland. Since then, other trails have been established at more than 675 government facilities, including one put up by Chuck Dupree (who was also involved in the founding of NABs) at the Goddard Space Center in Greenbelt, MD, and a small trail at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Long Island. (Forward to The Return of the Bluebird)

1974: Duncan Mackintosh of Lethbridge, Canada started the “Mountain Bluebird Trails, that extended into Montana, joining the efforts led by Art Aylesworth of Ronan, Montana. The group was incorporated as a 501c(3) non-profit organization in 1998. In eastern Canada, Leo Smith worked with several naturalist organizations to put up bluebird trails in southern Ontario. The Robert Braley family also put hundreds of boxes at Pike Lake in Ontario.

Aylesworth first got interested in bluebirds when he and his wife Vivian saw a flock of males sitting on a snow-covered pine tree. “They looked like big blue Christmas ornaments.” He started by building five nestboxes, of which one was used the first year. Eventually he got local lumber mills to donate scrap wood and recruited volunteers to build and put up and deliver boxes. In the next 20 years, Art and his Mountain Bluebird Trails volunteers built over 35,000 nestboxes and fledged over 200,000 bluebirds. (Source: A Passion for Bluebirds, Bob Niebuhr.)

1975: Bowater Carolina Company of Catawba, South Carolina, which was involved in lumbering and in wood pulp, paper, and other forest products, began producing well-made nestboxes and giving them with complete instructions to persons requesting them in the Carolinas and adjoining states who would agree to make proper use of them and report their results annually. More than 3,000 nestboxes were distributed under this program and the results have been highly encouraging.

Other utility companies joined in conservation movement by permitting placement of nestboxes on their properties or by actually establishing trails – e.g., Pennsylvania Power and Light Co. and Philadelphia Electric Co. .

The Northern Neck of Virginia Audubon Society, a chapter of the National Audubon Society, initiated a “Bring Back Bluebirds to Virginia” project, selling nestboxes with instructions  and a reporting form through local merchants.

and a reporting form through local merchants.

Keith Kridler of TX started making PVC nestboxes from left over plumber waste pipe on job sites.

1976: Larry Zeleny published The Bluebird – How You Can Help Its Fight for Survival. Zeleny estimated that bluebird populations declined drastically from the late 1920s-1970s. He estimated that the Eastern Bluebird population had declined by 90% over that period based on his own recollections and other friends of bluebirds who had lived long enough (From Bluebirds! By Grooms and Peterson). T.E. Musselman died, after more than 70 years exploring bluebird conservation and educating others.

1977-78: The coldest North American winter on record for the last 110 years. Some estimated 60% losses of bluebirds. (In Tennessee, losses may have approached 90%, according to Dr. David Pitts.) It can take 3-6 years for bluebirds to recover after a severe drop in numbers. Again, climactic events have a very significant impact on  bluebird populations. For example, the winters of 1977 and 1978 almost eliminated populations that had increased as a result of Godfrey’s trails in Illinois.

bluebird populations. For example, the winters of 1977 and 1978 almost eliminated populations that had increased as a result of Godfrey’s trails in Illinois.

June 1977: National Geographic published Larry Zeleny’s “Song of Hope for the Bluebirds.” It was the first article in a large, general interest publication to highlight the bluebird’s plight. It resulted in a groundswell of support.

1977: Junius Birchard of Hackettstown, New Jersey began a campaign to bring back the bluebird to that state. He gave talks to school children and adult groups. In addition he obtained and supplied at cost to interested persons precut lumber for constructing nearly 5,000 bluebird nestboxes, with instructions and demonstrations if needed. Through programs like this, teachers show children how they can become personally involved in helping a troubled species of wildlife survive. (Forward to The Return of the Bluebird)

1978: A small group of experienced bluebirders got together and formed the North American Bluebird Society (NABS), incorporated on March 20, 1978 (Sialia, 1:33-34.). NABS publishes quarterly journal. Zeleny was the official founder. The first 6,000 members came from those who had written to Zeleny over time in response to his articles, from US, Canada and Bermuda. Over the years, he had kept their letters in a closet in a couple of old paper grocery sacks.

Zeleny had tried to get the National Audubon Society to support a national bluebird preservation effort in 1976, but they declined. At the time they were established, there were no state bluebirding societies. For about 20 years NABS was pretty much operated out of Mary Janetatos house. (Keith Kridler, 2006)

NABs published a brochure “Where Have All the Bluebirds Gone.” One million copies distributed. They also produced an educational packet for middle schoolers called “Getting to Know Bluebirds.” NABS later worked to motivate more government agencies to get involved in bluebird conservation.

A later NABS brochure (date?) was entitled “Welcome Back the Bluebird.” It promoted the Transcontinental Bluebird Trail and explained about “NABS Approved” nestboxes.

Today they make slide shows that have been used in hundreds of programs. They sponsor research on sparrow competition, predation, brood failure, etc.

1979: “You can Hear the Bluebird’s Song Again,” written by Joan Rattner Heilman, appeared in Parade Magazine. As a result, NABS got 80,000 written requests for more information.

The US Fish and Wildlife Breeding Bird Survey reported that Eastern Bluebirds were “very rare” in many areas of the Midwest and East,

“rare” in other others, and “uncommon” in much of their original

range. (Scriven)

NABS conducted a continent-wide search for sparrow-resistant nestboxes. After testing, they concluded that only the PVC-pipe design had a deterrent effect while still attracting bluebirds and protecting their nests from inclement weather (Bluebird Monitors Guide p. 79) A plan for Bauldry open-top boxes (designed by Vince Bauldry from Suamico, Wisconsin) was published (as EX-1) but is no longer recommended because in colder, wet climates the design can result in nestling hypothermia and death, and HOSP may still use it.

The Midwest Bluebird Recovery Program began as part of the MN Chapter of National Audubon, and then became the Bluebird Recovery Program (BBRP) as Wisconsin, Iowa and Nebraska formed their own organizations. BBRP was the first NABS affiliate. They are still a committee of the Audubon Chapter of Minneapolis. (Scriven, personal communique 2006)

1981: Jeanne Price of NABS had sent a letter to the Citizen’s Stamp Advisory Committee requesting that the Postal Service issue a bluebird stamp. The request was turned down because stamps depicting all 50 state flowers and birds were scheduled for issuance in March of 1982, and the Eastern Bluebird was the New York and Missouri State bird, and the Mountain Bluebird was the Idaho and Nevada State bird.

requesting that the Postal Service issue a bluebird stamp. The request was turned down because stamps depicting all 50 state flowers and birds were scheduled for issuance in March of 1982, and the Eastern Bluebird was the New York and Missouri State bird, and the Mountain Bluebird was the Idaho and Nevada State bird.

1982: On April 14, 1982 the U.S. Postal Service issued a State Birds and Flowers 20 cent stamp series for all 50 states, with the bluebirds painted by Arthur Singer depicted on stamps for Idaho, Missouri, Nevada and New York.

Mr. Ira Campbell published an article in SIALIA, Vol.4, No.2, Spring, pages 49-51 on the Campbell blow fly Reducer, which he had been using since the late 1970s in VA. It uses a 3/8 hardware cloth screen near the bottom of the box, allowing larvae to fall through nesting material.

1984: Dr. Shirl Brunell self-published “I Hear Bluebirds,” the story of a pair of baby bluebirds orphaned as a result of a House Sparrow attack that Brinell adopted and raised. She was a clinical psychologist working with abused children. She found that some severely traumatized children could not connect with humans or her but they could connect with bluebirds that she attracted to her woodland clinic. Brunell passed away in 2005. (Kridler)

The Connecticut Bluebird Restoration Project (CBRP), a private nonprofit organization dedicated to restoration, conservation and management of native cavity-nesting birds. (CT Wildlife, July/August 2007) As of 2007, CBRP monitors up to 2,500 nestboxes and currently manages 700-800. POC: Dave Rosgen, White Memorial Conservation Center, Litchfield.

1980’s: Art Aylesworth and Duncan Macintosh led a campaign to convince NABS to recommend a larger nestbox with a 1 9/16″ hole for Mountain Bluebirds (Niebuhr).

1987: NABS started up a Speaker’s Bureau at the suggestion of Jerry Newman of MD, to help spread the bluebird word. After Newman, Kingston served as Chair from 1989-2007, followed by Jimmy Dodson.

1988: Ron Kingston invented the wobbling stovepipe baffle, which is still one of the most effective baffle styles to prevent predation by snakes and climbing predators.

1989: The Mountain Bluebird Trail volunteers built the Centennial Bluebird Trail, which runs 700 miles across Montana along Highway 200, from Idaho to North Dakota. (Niebuhr).

1990: Charles Ellis of Ellis Bird Farm, LTD died. (Ellis Bird Farm history)

1991, 1996: The U.S. Postal Service issued a 3 cent bluebird stamp as part of a “feathered friends” group. It was designed by Michael Matherly of Cambridge City, IN. 200 million were printed. The 1991 bluebird stamp and the 1 cent American Kestrel stamp were the first multi-color denominated stamps to be printed entirely by offset presses. (Sialia, Autumn 1991)

1992: Bluebirds Over Georgia was formed, with Frances Sawyer as the first President.

1995: Cornell’s The Birdhouse Network was launched to gather nestbox result data from citizen scientists.

Duncan J. Mackintosh died (1926-1995). He had established 722 miles of Mountain Bluebird Trails with more than 4,000 nestboxes that fledged an estimated 10,000 birds. (Harris)

Steve Eno and other bluebird enthusiasts formed Bluebirds Across Nebraska (BAN), which is now a hugely successful and active society.

Larry Zeleny died on May 27, 1995, at the age of 91. He had continued to monitor his 60+ nestbox trail on the grounds of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s Research Center in Beltsville, MD until 1992. (Source: NABS history)

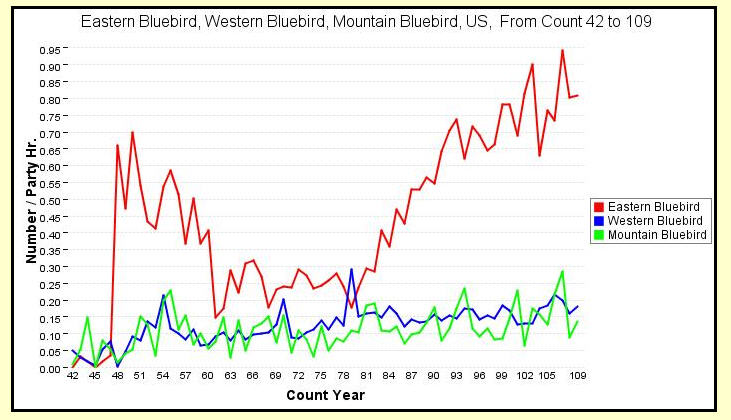

1996: Breeding Bird Surveys from 1966-1996 showed an average annual

increase of 6.9% per year in the Eastern Bluebird population (Scriven)

Chuck Dupree (treasurer who initially set up financial base for NABS) died on May 6, 1996 at the age of 76. (Source: NABS history)

1997: A Mountain Bluebird painted by Pierre Leduc appeared on one of the 1997 Birds of Canada 45 cent stamps.

1999: 21 bluebird organizations across the US and Canada were officially affiliated with NABS. Many others are independent. (Scriven)

The Eastern Bluebird was removed as a species of special concern from the New York State’s Endangered, Threatened and Special Concern species list (NYS Press release 5/11/99)

Art Aylesworth died (1927-1999).

2000: In partnership with Wild Birds Unlimited, NABS launched the Transcontinental Bluebird Trail (TBT) for cavity nesting birds. One year later, there were 18,587 registered nestboxes in a network of 360 trails U.S. and Canada. The world’s largest bluebird trail is probably the one stretching 2,000 miles from Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

The Massachusetts Bluebird Association was also formed this year.

Dick Peterson died on May 4 at the age of 81. Dorene Scriven reported that a pair of bluebirds appeared out of nowhere to fly above his grave, during the ceremony at Fort Snelling National Cemetery near Minneapolis. By that date, the Bluebird Recovery Program had supplied more than 12,000 people with copies of plans for the Peterson nestbox, and David Ahlgren had shipped out over 60,000 nestboxes or kits. (Bluebird, Vol.22, No.3, Summer 2000).

Floyd Van Ert made the prototype of the Universal Sparrow Trap, an extremely effective inbox trap for capturing House Sparrows. As of 2005, he had manufactured over 10,000 of them, along with designing traps for kestrel, purple martin, gourds and wood duck nestboxes. Van Ert had never seen a bluebird until 9 years earlier, but it’s not just the “old-timers” who are making a difference in bluebird conservation.

2002: Louisiana Bayou Bluebird Society formed.

2005: HR 4114 (an amendment to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act) was passed, addressing the Hill v. Norton court decision which would have extended Migratory Bird Treaty Act provisions to non-native invasive species including starlings and House Sparrows.

The amendment applies the Act only to native birds, providing state fish and wildlife agencies with the management flexibility they need to control nonnative, human-introduced birds that are causing serious ecological damage as well as causing serious harm to native birds. (Audubon Action, 2005)

A pair of Western Bluebirds nested in the Presidio in San Francisco. The last recorded nesting of Western Bluebirds in the city was in 1936 (Golden Gate Audubon Society. They do nest in other parts of the Bay Area, including Marin and San Mateo County.)

Ecologists attributed their return to the restoration of native dune plants in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

“It’s a testament that something right is happening, that people are making moves in the right direction toward attention to habitat restoration and the local ecology,” said ecologist Joshua Clark. (San Francisco Chronicle, 6/4/05)

The Mississippi (Mississippi Bluebirds) and Maine bluebird societies dissolved (NABS 2006)

Al Emmons of Greendale, WI, displayed a giant bluebird statue on his home’s chimney located at Bluebird Court. The Village’s Historic Preservation Board ordered Emmons to take the blue Big Bird off the chimney or face a $100 a day fine. Emmons removed it, but then put it back up on the roof with an American flag in its wing. (Local6 News.)

2006: Loss of open space and forest fragmentation continue. This has probably allowed the House Wren, a native bird which competes with bluebirds for nestboxes, to expand its breeding range considerably, especially in the southeastern United States. This little gremlin was first seen nesting in West Virginia and Kentucky in late 1800s, SW Indiana and SE Illinois in 1870, North Carolina by early 1920s, South Carolina and Tennessee by 1940s, north central Georgia, in 1950, central and south Missouri in 1960s, NE Alabama and Arkansas Ozarks in the 1970s, and Jacksonville AL in 1984. (BNA online)

Jack Dodson worked with Steve and Regina Garr to form the Missouri Bluebird Society. Missouri was the birthplace of the National Bluebird Trail.

Jack Finch died at the age of 89. In 1973, Home for Bluebirds Inc. assembled and distributed more than 60,000 nestboxes since 1973. He “was a pragmatic naturalist. He would build four or five houses with different designs and watch to see which ones the birds preferred. To develop snake guards, Finch built a huge snake pit and filled it with black snakes and corn snakes to observe their behavior. ” At one time Jack Finch was monitoring 2,200 boxes across North and South Carolina and Virginia. (The News & Observer, 11/11/06)

The Mountain Bluebird Trails group (started when Art Aylesworth put up his first five networks in 1974, and incorporated in 1998) reported almost 700 members and has fledged over 330,000 bluebirds, including 175,000 in the last decade (1997-2006). (Niebuhr, personal communication.)

2007: Dave Ahlgren passed away on March 13. He was deeply involved with the Minnesota Bluebird Recovery Program. He made more than 85,000 Peterson nestboxes and distributed them throughout Minnesota and across the United States.

The State of Missouri selected a license plate featuring a bluebird (the State bird.)

2008: Georgia bluebird society folded.

Don Yoder passed away on July 9, 2008. He was the Director of the California Bluebird Recovery Program in Rossmore, CA, and a member of the NABS Speaker’s Bureau. He started bluebirding in 1972.

2017: Michael Lindsay Smith, “The Mad Bluebird” photographer, and member of the Maryland Bluebird Society, passed away in New Windsor, MD.

Dr. Wayne Davis (b. 1930) from Kentucky, a tireless supporter of NABS and bluebirds, also passed away in 2017. Dr. Davis developed and placed over 3000 slot boxes along KY highways and in surrounding states. He and Dr. Roger Barbour authored “Bluebirds and Their Survival.”